In an earlier article, I discussed how big a landing site needed to be for UK and European Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) operations.

However, this is only part of the story and there is a lot more to choosing a landing site than just the size. Whilst this article is primarily focussed on UK HEMS, the process and logic apply in many helicopter realms where helicopters are operating in complex environments.

Contents

The acronym I currently use for assessing ad-hoc landing sites is 5SAD. Let’s look at how we get to this.

Improving on the 5S recce

Many UK military pilots will recognise that size is only step one of a process for conducting a thorough reconnaissance of a landing site from the air. The “recce” is a captured in the 5 S’s:

- SIZE

- SHAPE

- SURROUND

- SURFACE

- SLOPE

Thus a football pitch becomes:

“It’s a large rectangular green field, surrounded on all four sides by seating rising to about 30 ft. It is short dry grass and appears to be flat.”

That confirms to everyone on board that we are looking at same field, whether its big enough and what obstacles we might encounter on the way in. It also tells us if we expect to be able to land in a particular part of the site once we are in the landing area. It’s a method which has been proven in the most difficult of circumstances. However, it is missing some significant threats which means we need to add something else. To start, let’s look through what 5S gives us.

Size

Take a look at my earlier blog linked below. Basically, for day operations, it needs legally and practically to be at least twice the biggest dimension of the helicopter – called “2D”.

Shape

As discussed in my 2D article, the smallest shape we can land in is a 2D circle. But is that the best shape? Probably not! As can be seen from the last image, when we land in a minimum size area, the margins from the blades over the nose and from the tail are actually quite small. From a little simple maths, it will be 0.5D from each if the helicopter is central in the circle. That equates on the helicopter shown to be 6.5 m or about 20 ft.

I would like a little more margin than that if possible, particularly around my tail rotor which I cannot see or monitor from the cockpit. There is a natural tendency therefore to bias a landing towards obstacles in front, in order to protect the tail. A shape which gives me maximum space round my tail is preferable.

As an example, note how in the image below that the parking space markings have been used to judge where the tail has ended up. The EC135 is about 2 parking spaces long so the pilot can tell the tail is well clear of the building. This landing area is a big square. What about something a little more complicated?

In the next example we see a big green lozenge-shaped field. The helicopter has biased slightly towards the end and left this time. The helicopter is aligned to the longest length of the field, giving lots of space under the approach and lots of room around the tail.

But actually, look closer! Notice the telegraph pole behind the aircraft. Also look in the tree line just above the helicopter. There’s another pole. Between the 2 are nearly invisible wires making this a long thin field. The “shape” of the field is more complicated that just the edges of the flat bit.

But put simply, we want a big site with plenty of space round the tail. Open fields, sports pitches and car parks would seem to be perfect then.

Surround

Once we are in our field, size is good. But getting there can be a challenge. What is around our potential landing site can dictate a certain approach path or rule out the site altogether. Again let’s look at some examples.

In this example, the pilot has landed along the longest axis of the site, keeping plenty of room around the tail. This was also the approach direction. To the rear is a road with a layby but no footpath. The objects in this area are unlikely to be affected by downwash (except perhaps cycles and motorcycles) so it is a good choice for approach path (more on downwash later). The area to the left of the approach is domestic gardens. These are typically filled with many objects and people who are sensitive to sudden winds and best avoided on the way in – think trampolines, parasols and children!

To the right of the helicopter is a playground. Whilst downwash would make for a great swing ride, it is vital to ensure they are clear of kids before landing. If not, go somewhere else. The trees beyond the playground may be harmless, but their height and size can lead to a steep approaches and to hazards being obscured.

Sometimes the surrounds can be very grand but essentially wide open on all other sides. This presents a special hazard as access to the landing site is very easy. The medics can easily get out but the public can get in. It is impossible to monitor in all directions, particularly when leaving a scene without the medics. It can be quite unnerving to be only able to see in one small arc at such open sites. Fortunately most of the public are angels and listen to the crew.

So in summary, we want the area to be surrounded by short things that are not going to be affected by a helicopter dropping in or taking off. Open sites present a special hazard.

Surface and Slope

The last two items in the 5S recce are frequently lumped together. With Size, Shape and Surround we have looked around the site; now we are getting inside. The surface and slope is often really simple. Just look back up to the landing site in Bath – short, dry grass that is flat. Perfect. Same for a little tarmac – again spot on.

It is often not that easy. In the example below, a constant stream of heavy trucks had turned the mud in a fine, talc-like powder. The downwash of the helicopter is likely to pick up a huge cloud of the stuff (notice – we are back to talking about downwash – more on that below). Fortunately, the dust suppression measures at the site were working and the cloud was light and brief. The slight downslope was completely within the capabilities of the helicopter and the pilot.

Short grass is much less dusty, but the slope can be interesting. In the next example, the slope was right on limits – 12 degrees nose up in this case. This presents some challenges for rigid rotor aircraft like the EC135. It can also make loading a patient quite fun – as the patient slides into the aircraft on the stretcher, the slope can make them shoot to the back of the machine.

So something hard and flat is ideal but we can tolerate some variation.

Adding to 5S

So we now have enough information for our perfect landing site. That nice big green sports field is perfect. In we go!

Doh! The medics cannot get out! It’s a school football pitch and it’s surrounded by a 6 foot fence and it’s the weekend so it’s locked up tight. We need to consider something else as part of our recce.

Access

Being able to get from our landing site to our scene is vital. It is also important in many cases to be able to get back to the helicopter with a patient on a stretcher, on a back board or in an ambulance.

Gates

Looking for breaks in hedges, gates and paths is a crucial skill. If you can see a gate or a break in a fence then perfect. But sometimes you need to look at the ground. As an example in the shot below, you can see where the tractor tire marks suddenly go at 90 degrees to the hedge line – there is a gate there even though you cannot see it. Similarly people make marks in fields and you can find an exit that way.

Livestock can often be an indicator that you will struggle to get out of a field. Often there will be barbed wire or an electric fence surrounding their fields which is not ideal. This is before you have even considered how a helicopter might scare or injure animals.

Locks

Landowners like to protect their land and will lock it up. Many low gates to fields are padlocked and whilst paramedics enjoy vaulting over them on the way to a job, it is less convenient when carrying a patient back to the helicopter. A 6ft tall gate at a school or commercial premises is much more of an obstacle. We could snip our way through with bolt croppers but this is often not practical or neighbourly. Looking for a more open route to scene may be preferrable, even if it involves a longer transit into scene. In the example below, the large locked gate at the football ground would have blocked an exit from the otherwise ideal football pitch. The car park was a better option although it is amazing how many people then try to drive under the rotor.

Sometimes locks can work for the crew. In the example below, the 24 hr security at a factory worked in the crew’s favour. The aircraft was protected from the public and vice versa and the security team drove the crew straight to the nearby job in the security van. The photo was posed later!

What else needs to be considered?

Downwash

The flow of air from a helicopter in flight can be very dangerous. A lot of research into downwash (downwards flow) and outwash (horizontal flow) has been conducted recently (see CAP 2576 for example). There are several recent incidents that have brought this topic to the fore (see fatal incident at Plymouth Hospital – Aircraft Accident Report AAR 2/2023 – Sikorsky S-92A, G-MCGY – GOV.UK). As helicopter operators using ad-hoc sites, downwash and outwash need to be considered in every case.

Vertical flows – Downwash

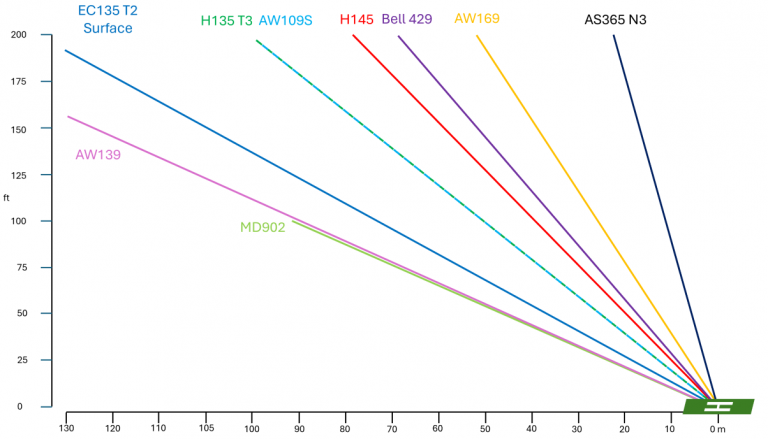

Typically for HEMS operations, a steep or vertical landing and take off if used due to the obstacle environment. In HEMS we can operate in Performance Class 2 which gives a degree of choice to help minimise the downwash threat, but the baseline is often to use the Cat A certified helipad profiles (see my article about backup distances for a comparison of the profiles of HEMS aircraft – It’s behind you! Helipads and obstacles in the backup area).

These profiles are designed to address the threat of a single engine failure, but are less suited to minimise the effects of downwash on 3rd parties. Take the AW109 helipad profile as an example. From 120 ft agl (LDP plus obstacles), the aircraft is 60 m back from the landing spot. 120 ft is roughly the height below which downwash will touch the ground during a landing. So if we stick with the Cat A profile, we drag our downwash across the ground for a substantial distance on our way into the landing site. So what?

Look at the following example. If a standard AW109 profile had been used in this case, the downwash would have gone straight into the back gardens of the properties behind the helicopter. A steeper approach or even vertical profiles are often preferrable as it keeps the downwash contained in the close vicinity of the scene.

Horizontal flows – Outwash

We also need to consider the outwash of the helicopter as the downwash starts to interact with the surface. Outwash for single rotor helicopters typically goes out to roughly 3-times the size of the rotor disc (take a look at Jopp’s article here for more on downwash – Understanding Rotor Downwash: The Ultimate Pilot Guide). In the example above, the footpaths, playground, trees and properties will all be affected. Items such as umbrellas, trampolines, wheelie bins and rubbish can all be picked up and thrown outwards and upwards. The effect is greatest during landing and take off but can be minimized when in a low hover.

With this in mind, it can be effective to approach to the centre of a large field and then hover taxi towards the best exit, monitoring the effects of downwash. In the example below, there was no need to approach right next to the incident in the layby; the approach was made to the middle of the huge field and then the aircraft was air taxied closer to the exit from the field.

The wind also needs to be factored in. Downwash and outwash are subject to been blown downwind. In one memorable incident in a park, the aircraft was landed at one end of a field on a light wind day. The outwash stayed fairly coherent due to these light winds and travelled as a vortex right the way along the field out to around 150 m and blew every single parasol off the tables at a café right at the other end. Another consideration to add to the recce perhaps?

5SAD – A vital tool for HEMS crews

To summarise, adding Access and Downwash to our recce gives us:

- Size

- Shape

- Surround

- Surface

- Slope

- Access

- Downwash

5SAD is a great tool for ensuring risks have been considered at a HEMS site before committing to land. What tool do you use? Share in the comments section below.

A few last thoughts

Whilst a good recce is important, insider knowledge can help too. Here’s a few thoughts on some typical landing site options:

- School fields – great inside school hours as they are large and flat but the risk of harm from downwash needs to be considered. Out of hours, the 6 ft locked gate can be a problem – work with the schools to gather codes and keys for important sites.

- Car parks – nice and flat but there are often hidden pedestrians, light poles, sign posts and kerbs to get in the way. Some people will also not care or hear that you are landing and will drive at you!

- Cricket pitches – the crease is often roped off with re-bar metal stakes. The roller covers and barriers are often unsecured and can roll or blow over due to downwash.

- Artificial pitches / 5 aside pitches – the wires used to hold curtains between pitches are extremely difficult to see. The rubber pieces hiding in the grass can be a FOD risk and may take a very grumpy grounds person a long time to put right when you’ve left.

- Bowling greens – the wrath of the bowlers if you make a dent will likely make it unwise to land here.

- Car boot sales – the aircraft can be mistaken for an open house – prompt assistance from the Police may be needed to keep the hordes back

- Hills – land at the top and the medics have an easy walk down but a slog back up with the patient. Land at the bottom and its an exhausting walk up but easier to carry a patient down. Why not do a full recce and landing at the bottom, then reposition to the top to drop the medical team. Now fly back down and wait for them – gold star for the pilot!

Now you’ve read that, take a look at my other articles:

- Post Maintenance Flight Tests – How to avoid fatal traps

- First Limit Indicators in Helicopters – Deadly mistakes to avoid

- Bad Vibes – How to report vibrations on helicopters

- Autopilots, cross-checks and low G in helicopter unusual attitude recovery

- Expert site surveys – Improving the assessment of onshore landing areas

- Lights, helipad, action! The problem with new helicopter pad lights

- Helicopter on Fire – Could accident investigators have learned more?

- The Ultimate Medical Helicopter – Selecting the right machine for HEMS

- Aerial teamwork – Practical tips for working together by staying apart in emergency aviation

- HEMS Landing Sites – Reliable places to drop your medics

- Planning to fail – The perils of ignoring your own advice

- 2D or not 2D – How much room do I need to land a helicopter?

- What is your left hand doing? How to fly a 3-axis autopilot on helicopters

- My tail rotor pitches when it flaps! Why?

- Practical ILS explanation for pilots – the surprising way they really work

Leave a Reply