In the modern helicopter era, some helicopters have Flight Data Monitoring (FDM) and Helicopter Usage Monitoring Systems (HUMS). This means engineering teams have vast amounts of data to diagnose issues with helicopters. However, many helicopters do not have these systems. In other cases, a pilot’s experience of a fault can unlock the solution to a fault.

This is particularly true when it comes to vibrations. In an inherently shaking machine, pinning down one abnormal vibration can be a hard task. A pilot report of “It’s a bit shaky” is not likely to be helpful and can lead to a frustratingly long diagnostic process. Contrast with a report that describes “It’s a vertical bounce at 1R, worse below 50 kts which is immediately apparent to the pilot as the instruments shake” – the engineers now know it is likely a main rotor tracking problem.

But what is 1R? That description of the vibration is a bit subjective – could we objectively compare the reports of 2 pilots? Let’s dig into into the topic a bit deeper.

Contents

Sources of Vibrations

Helicopters vibrate – it is a fact of life. There are many sources of vibrations on helicopters which are caused in normal operation by:

- Main rotor

- Tail rotor or Fenestron

- Rotor gearboxes

- Engines

- Engine gearbox

- Pumps

- Undercarriage (eg shimmy on steerable nose gear)

Abnormal conditions or issues can modify existing or create new vibrations:

- Ice accretion and shedding from blades

- Damage to blades

- Foreign objects inside rotor cuffs/rotating parts (eg water in EC135 blade cuffs)

- Loss of parts

- Damage to other components of rotor head (eg pitch change links)

- Out of track/balance blades

Vibration Definitions

In order to discuss and compare notes regarding vibrations on helicopters, we need a taxonomy for the various aspects of those vibrations:

- The frequencies of the vibrations – collective terms for the oscillations

- The relationship of vibrations to rotating parts such as the main rotor, tail rotor and gearboxes

- The direction of the vibration such as vertical or lateral

- The continuity of the vibration – is it continuous, intermittent or related to a particular range of flight conditions

Frequency ranges

Very Low Frequency Vibration

Vibration with a frequency below 5 Hz is a very low frequency vibration. Examples include the fuselage shuffling about on the ground. An inspection of the landing gear or main rotor may be needed. This type of vibrations can be quite uncomfortable and nausea inducing (think of rocky boat).

Low Frequency Vibration

Vibration between approximately 5 to 20 Hz is a low frequency vibration. This includes the natural operating frequency of components such as the main rotor. Typically this is discussed as a vibration that happens once per revolution or 1/rev or 1R. This ranges from 8.8 Hz on an R22 down to 4.3 Hz in the cruise on an S92. When it gets obvious, it could be described as a repetitive “thump, thump, thump” vibration or a “rough” ride. An inspection of the main rotor and a track and balance run are likely actions.

Medium Frequency Vibration

Vibration between approximately 20 to 60 Hz is a medium frequency vibration. The vibration caused by the passage of each blade in a main rotor would fall in this range. It is described as 4/rev or 4R for a 4-bladed rotor and 5/rev or 5R for a 5-bladed rotor (and so on). It could be described as a thrumming type vibration. Rotor blade contamination might cause a vibration like this – see the rotor blade below which encountered heavy pollen at a field site. It’s also the vibration you get during normal approaches as you reach 30-40 kts.

Again, the main rotor or its associated rotating components are a likely source. This type of vibration is also the normal focus of vibration damping systems on helicopters, so the serviceability of these components needs to be checked. For example, the Frahm damper on a Bell 429 is designed to reduce the 4R vibration for the crew and passengers – a failure of the damper would likely result in an increase in the 4R.

Medium frequncy vibrations can also be related to the tail rotor once per revolution frequency (called 1T) although this does not feature as much in vibration issues as the 4R.

High Frequency Vibration

A vibration above approximately 60 Hz is a high frequency vibration. This might be related to the 4T frequency of a 4-bladed tail rotor (and so on). It’s often described as a “buzzing”, particularly on fenestron which has a much higher rotational speed. In the example below on LN-OOD in 2007, there was likely a very noticeable buzzing vibration after the damage to the Fenestron blade tips.

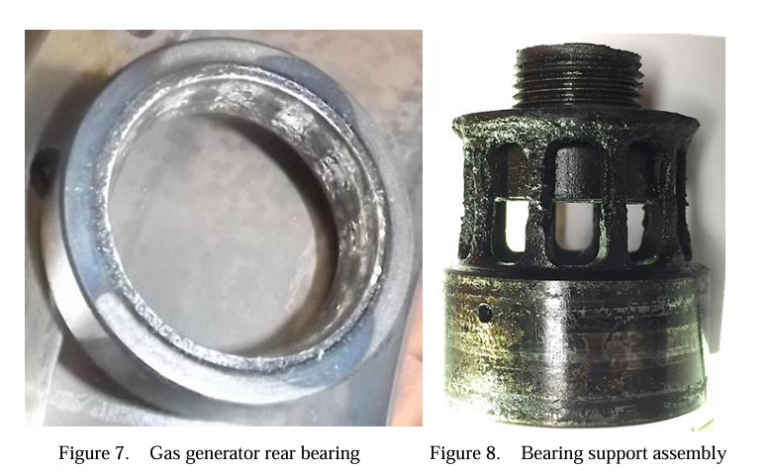

Also in this range are the various gears in the gearboxes and engines (which might be a howl, whine or screech). As discussed in our article on the Helicopter Fire – Could accident investigators learn more?, the breakdown of a bearing likely caused some vibration and noise for the crew. The incident involving N911Mk where a bearing broke down also likely including some vibration clues before failure:

A high frequency vibration can also be something entirely different. A strap lodged in a door might cause a hellish noise and sound which is closely linked to the aircrafts speed and will likely come from an unusual direction. This is generally not a good thing!

Directions of Vibration

The direction that the crew perceives a vibration to be in can be very useful in diagnosing the source. Some helicopters, such as the Bell 429, provide guidance on the likely corrective measures for vibrations in a particular plane – pitch link adjustment or tab adjustment for a vertical vibration but balance weight adjustment for a fore-aft shuffle.

Lateral vibration

A movement perceived by the crew as being side-to-side. Likely due to the main rotor being out of balance

Vertical vibration

A motion at the pilot’s heel or seat that usually indicates a main blade is out of track. This can be described as a “vertical bounce”

Fore-aft vibration

A fore-aft vibration is again likely to be a main rotor balance issue. This might be felt as a “nodding” motion

Transient or Continuous

Whether a vibration happens all the time, is transient or occurs only in certain conditions can be vital in pinning down its source. For example a failure of lead-lag dampers might be especially obvious during rotor starts and stops as the rotor gets accelerated or decelerated. A vibration that comes and goes seemingly at random can be very difficult to trace!

What is Normal?

Starting out on a new helicopter during a pilot’s career can be especially challenging with respect to vibration because what is normal has not been fully established yet. This is particularly true for pilots predominantly trained in a simulator as the simulator is unlikely to represent the real lived experience (they do try!). A significant change in aircraft size or performance can also leave a new pilot without a basis for comparison – “Does it always shake like this?”

Counter-intuitively there may also be occasions when the absence of a vibration is the abnormal thing. The structural failure of a component might give an odd “disconnected” feel to the vibration of a helicopter, becoming more smooth.

Real aircraft experience is the only real way to build up a knowledge of what is normal, along with advice from instructors as part of type rating or line training.

Assessing the strength of vibrations

When a component fails, there is sometimes a nice clear indication that it has done so; perhaps a caution or a total inability to get any response from a control panel. However, with a vibration, reporting the issue to the engineering team is difficult. Once the aircraft is shutdown its impossible to demonstrate the issue to an engineer. This can lead to an issue being monitored pending some more data.

This might mean a different crew operates the aircraft next and they mention the vibration again (hopefully using a comprehensive description as above). But has it got worse? Is it so bad we need to ground the aircraft? Can we just live with it? Was the vibration due to some external factor such as a storm?

These type of questions call for a method of describing the intensity of a vibration to allow comparison between observers and to drive the urgency of an engineering investigation.

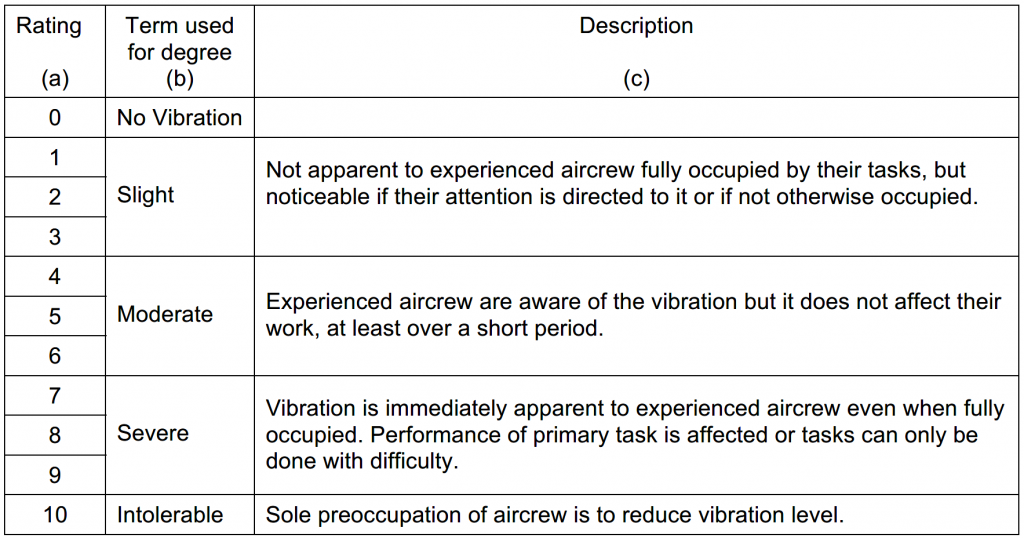

Vibration Assessment Rating (VAR)

Fortunately, a scale exists. The Vibration Assessment Rating (VAR) scale was developed by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) to assess vibrations during the flight testing of new, experimental or developmental aircraft. It is a simple scale that allows a pilot to assess the effect of the vibration on their operating task. This is taught to Test Pilots at ETPS but is a useful tool for any pilot.

To use the scale, you need to read the descriptors for each layer or degree then assess how close the vibration to cross into the neighbouring zone. This lets you chose a number. In simple terms, the degrees of slight, moderate, severe and intolerable are “Oh, that vibration”, “Aware but no problem, “That’s starting to be distracting” and “Get me out of here, I’m a pilot”.

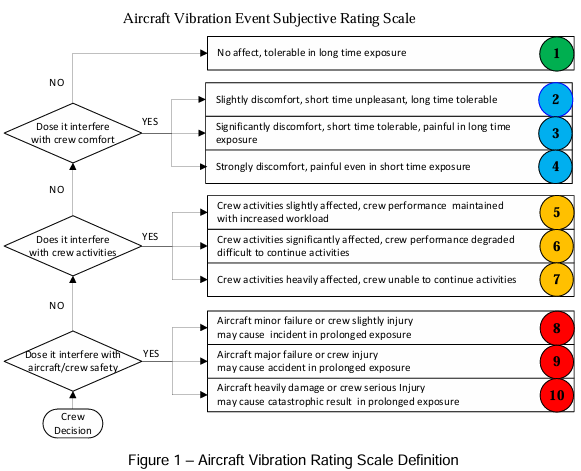

Alternative Scales

A similar scale can also be represented in a similar way to the Cooper-Harper Handling Qualities Rating scale as shown in this extract from Haigang Wang’s paper on vibration assessment here at ICAS. In this version, the pilot starts at the bottom left and answers the questions and compares the descriptions to come up with a rating for the vibration. Note the scales are not interchangeable!

Pilot Vibration Report

With all these tools at our disposable, a pilot’s report of vibration can now include a lot more colour and nuance, that can assist the engineering team with making rapid diagnoses and proportionate airworthiness decisions. Let’s look at a few examples of how we can bring this all together.

Vibration Scenario

Flight 1

The aircraft has been operating without issue for some time. A pilot notices a slight increase in 1R rotor vibrations in forward flight as the airspeed goes above 60 kts. It’s only noticeable when the pilot isn’t occupied with another task and has a vertical feel to it. Aside from speed, the environment or pilot action does not seem to change the vibration.

The pilot’s report to the engineering team is:

“I think the vibration levels on this machine are a little higher than normal. Above 60 kts, the 1R vibration rises from a normal VAR 1 to VAR 3. At maximum level speed it increases to VAR 4. There’s no perceivable track and it is about VAR 1 in the hover. It feels more vertical than lateral” – Pilot 1

The engineering team do an inspection and don’t find a fault. The track and vibration kit isn’t currently available, so they are content to monitor due to the low levels of the vibration.

Flight 2

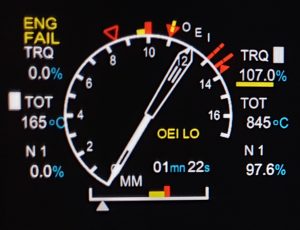

A few sorties later another pilot finds the vibration has changed. Now the vibration is immediately apparent on reaching 40 kts. At maximum level speed the vibration is causing the instrument panel to vibrate but the displays can easily be read. There is definitely a vertical component to the vibration. It is not apparent in the hover or on the ground.

The pilot report is:

“That vibration pilot 1 reported is still there. Above 60 kts, the 1R vibration rises sitting around VAR 3-4. At maximum level speed it increases to VAR 6 – the instrument panel is shaking. It goes away in the hover and back on the ground. I would call it a vertical bounce” – Pilot 2

Flight 3

Now the engineers have their track kit and they put it on the machine. Nothing is visually wrong on the inspection. Pilot 1 is picked to go do the air test. During the test the pilot is not happy with the vibrations the aircraft starts to accelerate and returns to base.

The pilot report is now:

“I had to abort the flight. The vibration level approaching 70 kts was a solid VAR 5, as I started to increase speed further it felt like a strong vertical bounce at 1R with VAR 7. Something is definitely wrong.” – Pilot 1

Through the use of a detailed vibratory description and a scale to allow comparison, it is now obvious that further flight is not a good idea. A detailed strip down of components or other testing will be needed before further flight is considered.

Without such detailed and structured feedback it is completely reliant on the relationship between the pilot and the engineering team against the weight of commercial pressure to decide when grounding the aircraft is necessary.

Conclusion

The aim of this article is to provoke reflection – is there a mechanism in your organisation to accurately and objectively report vibrations? Can you compare the opinion of a 10000 hr old hand with a 500 hr new guy without it coming down to “It always does that”?

Check out our earlier posts below:

- Keeping up with the Norwegians – Six amazing innovations for UK HEMS

- LNAV/VNAV (SBAS) – Are they approved for use in the UK?

- Helicopter 2D IFR approaches – Is CDFA the best choice?

- Understanding Helicopter Flight Manuals – Everything you need to operate safely

- Post Maintenance Flight Tests – How to avoid fatal traps

- First Limit Indicators in Helicopters – Deadly mistakes to avoid

- Bad Vibes – How to report vibrations on helicopters

- Autopilots, cross-checks and low G in helicopter unusual attitude recovery

- Expert site surveys – Improving the assessment of onshore landing areas

- Lights, helipad, action! The problem with new helicopter pad lights

- Helicopter on Fire – Could accident investigators have learned more?

Leave a Reply