You might be thinking that you understand a helicopter flight manual. Some limitations, some normal and emergency procedures, a bit of performance and a perhaps a few systems descriptions? Simple? However, as soon as any optional equipment gets added to an aircraft it gets very complicated. Without a thorough understanding of how civilian flight manuals work and how to read them, you can easily become an ad-hoc test pilot, flying the aircraft beyond its cleared limits.

In this article, we are going to cover where a Flight Manual comes from, how it’s structured and how adding some aircraft modifications makes the pilot’s life very difficult! It applies equally to fixed wing aviation as well as helicopters but we are just going to stick to helicopters for now.

Contents

What are Flight Manuals?

A Flight Manual is part of the official document set that is produced during an aircraft’s certification and is the authoritative source for information to allow safe operation of the aircraft1. For helicopters, the document is most correctly called a “Rotorcraft Flight Manual” (RFM) as this is the language used in the regulations that bring them into being.

Do we have to have Flight Manuals?

The requirement for RFMs to exist spawns from the same place as any other requirement for a helicopter – the Certification Specifications (CS). These are broken down into 2 weight classes; below 3175 kg requirements are in CS-27, whilst larger helicopter requirements are in CS-29 for UK/EASA. There are similarly documents called FAR-27 or FAR-29 for the FAA in the USA.

The requirements in CS-27 are less stringent than those in CS-29, which incidentally leads to an associated jump in acquisition and operating costs between aircraft with masses just above and just below the mass threshold of 3175 kg. For this article we are going to focus on CS-29, although the CS-27 requirements for Flight Manuals are nearly identical.

In CS-29 at paragraph CS 29.1581 it lays out that every certified helicopter must be provided with a RFM. It goes on to say what must be in the RFM (the “approved” sections) but allows that manufacturers may include extra data (the “unapproved” sections). This means that for the pilot every Rotorcraft Flight Manual should have the exact same core collection of data. Well sort of…

What is in Flight Manuals?

The part of CS-29 dealing with RFMs lays out the required information but is actually a little light on information about how it should be presented (29.1581 to 29.1589). This is because in a similar way to the Aircrew and Air Operations regulations, there a set of Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and some guidance (called “Miscellaneous Guidance” or MG in the CS). But that is not the only guidance.

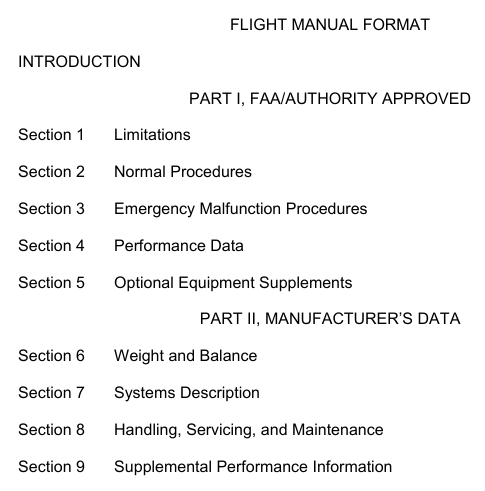

In a slight quirk of regulation, both EASA and the UK CAA actually directly reference the US FAA guidance material for both CS-29 and CS-27 helicopters. This guidance is published by the FAA in the form of Advisory Circulars which are helpfully titled AC-29 and AC-27 for each weight class of helicopters respectively. These ACs lay out much more guidance on how a RFM should be laid out including a proposed ordering of chapters.

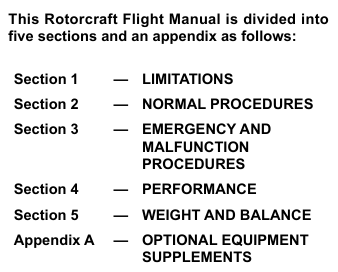

The Bell 429 RFM closely, but not exactly aligns to this “standard layout”:

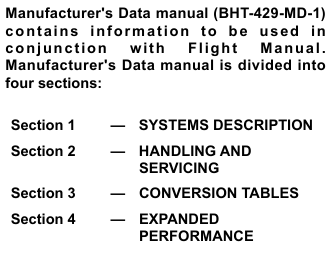

However, as with any AMC or guidance material there is scope for manufacturers to deviate to suit what they think the customer wants. So for example, in Airbus Helicopters the ordering of the RFM (called a Flight Manual (FLM) by Airbus) is:

What is safe to say is that every manufacturer lays out their RFM in a different way and saying “The emergency procedures are in section 3” is likely only going to apply to some manufacturers! Pilots need to become very familiar with the respective manual as part of type rating.

Aircraft Manufacturer Supplements

The “basic” RFM is reasonably easy to comprehend. It has an index and is laid out in a series of chapters. Whilst the ordering might be different between manufacturers, the limitations are likely near the front and easy to find.

This is fine, right up and until we do particular types of operation such as those requiring Category A certification (see the excellent paper by the Royal Aeronautical Society which explains what Category A means) or we modify the helicopter.

Example of Manufacturer Supplement

Let’s say we want to add a hoist system to the helicopter. The helicopter manufacturer wants to sell helicopters so it works with hoist manufacturers to provide an optional hoist that customers can select at the build stage or during service. The information to operate the modification is presented in a Rotorcraft Flight Manual Supplement (RFMS) branded by the aircraft manufacturer.

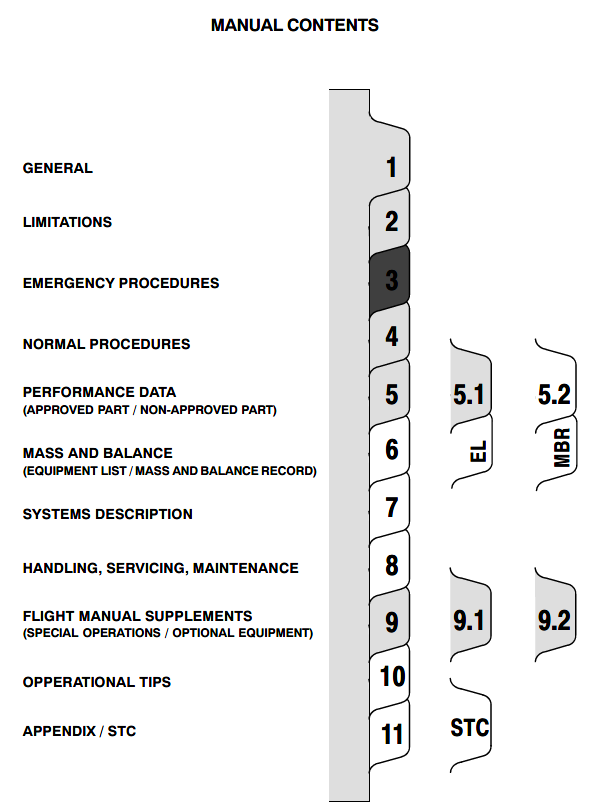

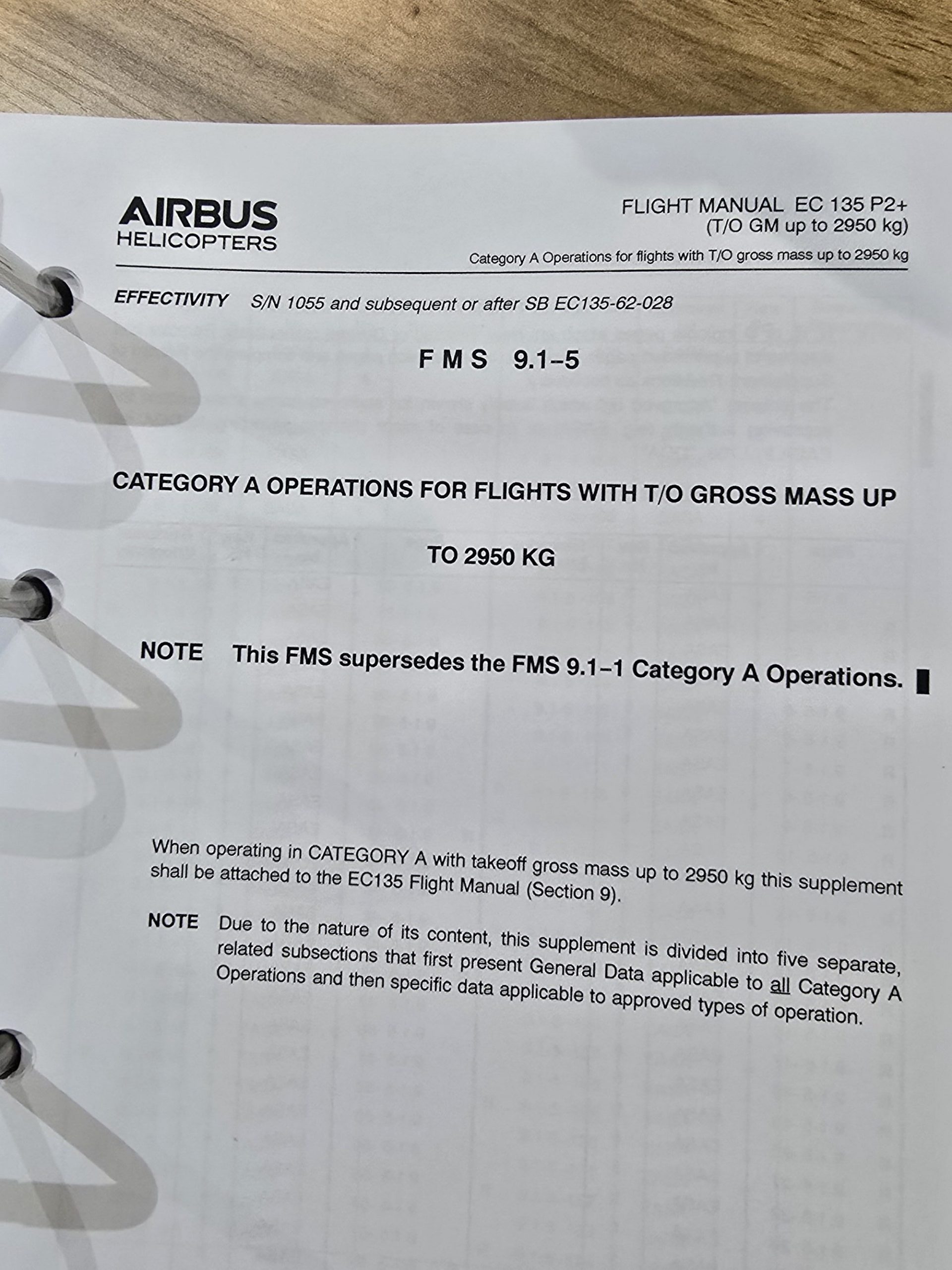

These RFMS are supplied in a dedicated section of the RFM (eg section 9 for Airbus Helicopters). For example on the EC135 T2 (CPDS) there are about 100 supplements for various modifications, which have been cleared for use by Airbus Helicopters.

These Airbus supplements, look and feel like the “basic” RFM because Airbus is the Type Certificate (TC) holder and it created the “changes” to basic Type Certificate.

Structure of Manufacturer Supplements

Each manufacturer supplement is structured in exactly the same way as the “basic” RFM. Taking our hoist example (Supplement 20 to the EC135 T2 manual) it contains:

- Section 1 – General

- Section 2 – Limitations

- Section 3 – Emergency Procedures

- Section 4 – Normal Procedures

- Section 5 – Performance

- Section 6 – Mass and Balance

- Section 7 – Systems Descriptions

So all very predictable about how to find things in the supplement. The whole supplement is self contained in Section 9 of the main RFM. But this creates a huge problem!

Combining Supplements with the core Rotorcraft Flight Manuals

Each manufacturer supplement is effectively a mini self-contained Rotorcraft Flight Manual. Now, in order to understand the limitations of the aircraft, the pilot needs to look in Section 2 of the basic RFM and the Section 2 of the RFMS for the hoist. Each part of the RFMS can be an addition, a restriction or a modification of the original RFM.

For example for the Airbus hoist system on EC135, the double generator failure emergency procedure has extra actions due the effects on the hoist.

Dual generator failure

- Hoist operation – Stop

- Emergency procedure according to basic Flight Manual – Perform

Before landing:

- Load – Set down at nearest adequate site

- Cable – Raise manually, store cable in the cabin

There is a more restrictive flight envelope (eg a speed limit of 60 kts with the hoist deployed) with the hoist deployed and a reduction in climb performance (about 30 ft/min at VY).

For one modification this is complex but not an insurmountable problem. However, once more than one supplement is applicable or we do not fit some manufacturer modifications we have some problems: which RFMS apply and what is the sum total of the RFM and RFMS put together.

Which RFM supplements apply?

The RFM is provided to allow the pilot to understand the helicopter (it actually specifically says in AC-29 that an RFM should be written in language the pilot can understand). When we have non-applicable manufacturer supplements we need to ensure the pilot only looks at the ones that apply.

This is a huge problem with electronic RFM supplied direct from the aircraft manufacturer. A pilot sitting in the comfort of the crewroom cannot tell which RFMS apply to their aircraft. This is solved to a certain degree in physical form in that only the relevant RFMS are actually left in the physical hard copy folder. This does need very careful management to ensure the right ones are included. Unfortunately there is not usually a nice neat list supplied anywhere and it needs sustained effort by the compliance team to keep things in check.

Let’s assume our careful pilot has been out to the aircraft and thumbed through to see what limitations from the supplements apply. With perhaps 20+ supplements on a typical aircraft it’s a diabolical task to assimilate 20+ limitations sections into one consolidated whole in pilot’s head. This just is not practical.

This is where the operator’s Operations Manual Section B can save the day by consolidating the limitations for the operating crew for the modifications relevant to the company’s aircraft. Take a look at ORO.MLR.101 for details about what should be in the manual.

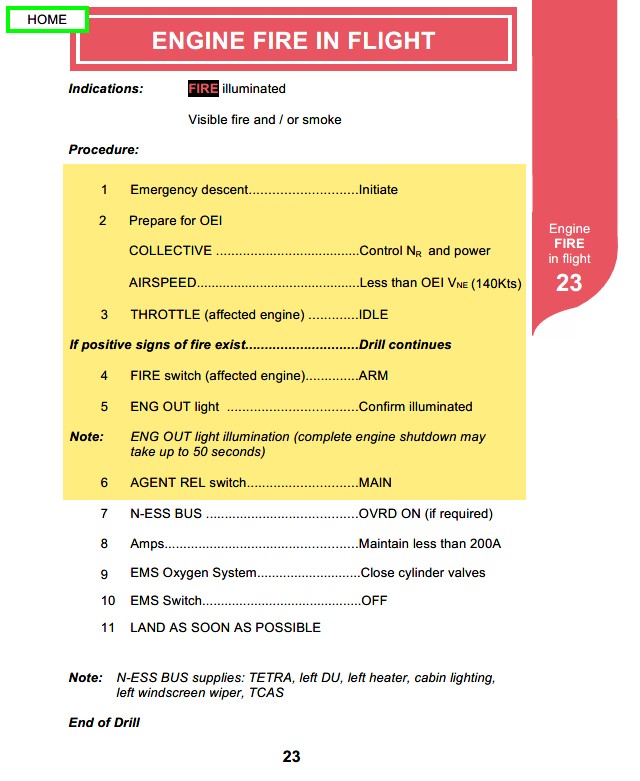

An Emergency Procedure Nightmare

But what about an emergency in the air? It is impossible to reference 20+ separate emergency sections of the RFM and RFMS during an emergency. This is why it is vital for operators to create a suitable consolidated emergency procedures list for the operating crew. It should be a carefully curated list of emergency procedures applicable to the as-modified state of the company’s aircraft, taking into careful consideration of whether the RFMS add to, replace or limit any emergency procedures.

Some manufacturer try to help operators by providing a consolidated set of emergency checklists which cover all the emergency procedures that are in the main RFM and in all the manufacturer’s RMFS. This means some emergency procedures will say “If mod A is fitted do this. If Mod B is fitted do this”. This can lead to an unwieldy set of checks.

As we have already discussed in our article EC135, Checklists and the “Red Button of Doom”, the Airbus emergency checklists for EC135 cover both basic VFR only SAS-equipped machines and full single pilot IFR AFCS equipped machines. The same emergency on a VFR machine can have a completely different procedure than on the IFR machine (in particular autopilot issues like a SAS actuator failure). In some cases applying the VFR procedure in an IFR scenario can lead to loss of control.

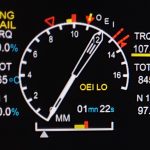

Compare the procedure from the VFR only aircraft as found in the Airbus-supplied emergency checklist (effectively completely dump all stabilisation):

Now look at the IFR-capable machine checklist for the same emergency – effectively do nothing but this is stashed away deep in an RFMS:

Operators need to approach use of these manufacturer provided cards with an abundance of caution. But it gets worse!

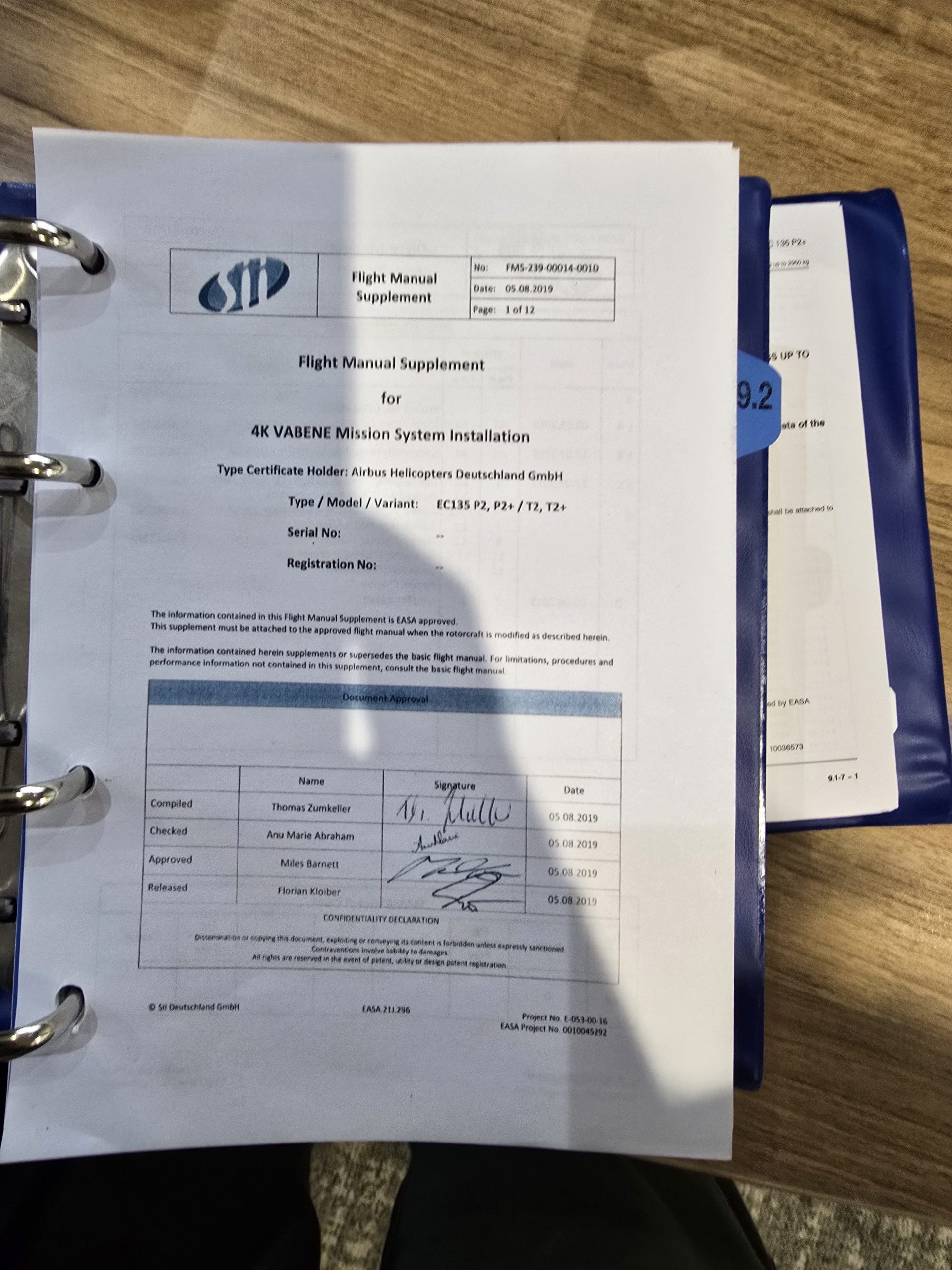

Third Party Flight Manual Supplements

The process for the TC holder to clear a modification is complicated. They need to consider all the possible combinations of their own supplements to see if modifications will work together and they need to weave together all the possible variations. For example, in the hoist modification RFMS on the EC135, at least 7 different RFMS are referenced and they modify the procedures for the hoist. The sheer number of cross-references is huge.

A 3rd party approved design organisation can consider a more limited scope and clear a modification onto the aircraft as a Supplementary Type Certificate (STC). This process also allows more variation – the manufacturer provides a mod for a sensor turret on the left – the operator wants one on the right – time for an STC!

This 3rd party modification process occasionally goes very wrong – see Mentour Pilot’s recent video about Swiss Air 111 where an In Flight Entertainment system installation led to a fire). However, there are strict oversight requirements in Part 21 of the regulations that ensure these installations should be just as safe as modifications by the original aircraft manufacturer.

In any case, as part of the process, the 3rd party design organisation still needs to provide an RFMS to provide the operator with the necessary information to use the modification safely.

Modified emergency procedures

As discussed already, the emergency procedures for the aircraft are a sum of the RFM emrgency section and the emergency section of any supplements. 3rd party RFMS make this a whole lot more complicated!

Take the example of the aircraft manufacturer supplied emergency checklist. This will definitely not contain the emergency procedures found in the STC based RFMS. Does the operator provided a supplement to the main emergency checklist which makes for a very cumbersome checklist. Or does the operator make their own bespoke checklist?

These bespoke emergency checklists can create a huge workload and risk of error as the operator is now responsible for tracking changes in the manufacturer’s list and all of the 3rd party’s RFMS!

However it is essential to consider a customised list. Consider HEMS or Air Ambulance where oxygen systems mean some emergency procedures have hugely critical extra procedures to turn off the oxygen in the event of a fire! These just are not considered in the core emergency checklist and simply will not get done in a crunch!

Different RFM supplement structures

The 3rd party organisation does not need to keep to the same RFMS organisational structure as the original manufacturer! They can order their supplement in a completely different order within the restrictions of CS-27 or CS-29 as appropriate. These supplements now add a huge level of complexity to the situation!

Which RFM supplement is relevant?

There is also the risk of confusion. What if both the original aircraft manufacturer provides a modification which seems very close to a 3rd party’s modification? This often occurs with NVIS modifications. The aircraft manufacturers modification could have wildly different limitations to the 3rd party one. This is the huge risk of pilots only referring to online PDF versions of the RFM – they must familiar with the RFMS for the actual modifications on their aircraft.

Let’s look at an example. On the H145 D3, the Trakka A800 searchlight is cleared for use on the left hand skid by Airbus under RFMS 9.2-14.

However, should the operator want the Trakka on the right, they need to approach a 3rd party design organisation and get a right hand installation cleared. In this case it was completed by Babcock’s Design and Completions Part 21J organisation so the crew need to use that RFMS.

There is no easy solution, but it is not a task to be brushed under the table and ignored. A careful RFM configuration management solution is needed within each operator.

Are the RFM supplements up to date?

Typically an aircraft manufacturer will have a robust document update and distribution system for ensuring every existing RFM is kept up to date. This can be quite costly for the operator! This system of distribution normally extends to all the aircraft manufacturer’s RFMS. However, this process can be patchy at best with respect to the RFMS for 3rd party STC.

The design organisation is meant to keep all users of its STC up to date, but this process can fall down leading to potentially incorrect versions of RFMS being used. Operators need a process to ensure updates are “pulled” from the relevant design agency.

A proposed way forward

Each operator needs to understand the totality of the RFM they have for each aircraft and its impact on the flight crew Several essential actions are required by each operator to minimise the risks:

- Comprehension – The operator should know exactly what supplements are applicable to each aircraft in their fleet and maintain a consolidated list

- Document assembly – The operator needs to ensure the RFM provided in each aircraft is an accurate representation of the as-modified helicopter. All the component parts need to be at the correct amendment state

- Operations Manual – The Operations Manual, specifically Part B, needs to be updated to reflect the totality of the RFM and all relevant RFMS. This may need modification to the limitations and Minimum Equipment List (MEL) sections. Aircrew training in Part D may also need amendment.

- Normal Procedures – The operators normal checklist should be modified to incorporate a consolidated list of normal procedures as relevant to the as-modified aircraft

- Emergency Procedures – The operator needs to make some challenging decisions about how to provide flight crew with the right emergency procedures for the aircraft. It’s usually either the manufacturer checklist plus a supplement or go the whole way and make your own. With the possibilities of EFB-hosted hyperlinked digital checklists (see example below), the latter solution should be considered by more organisations.

Hopefully this gives some food for thought. Go and check your emergency checklist – does it cover all your modifications? Is there an oxygen leak drill?

Now take a look at our other articles

- LNAV/VNAV (SBAS) – Are they approved for use in the UK?

- Helicopter 2D IFR approaches – Is CDFA the best choice?

- Understanding Helicopter Flight Manuals – Everything you need to operate safely

- Post Maintenance Flight Tests – How to avoid fatal traps

- First Limit Indicators in Helicopters – Deadly mistakes to avoid

- Bad Vibes – How to report vibrations on helicopters

- Autopilots, cross-checks and low G in helicopter unusual attitude recovery

- Expert site surveys – Improving the assessment of onshore landing areas

- Lights, helipad, action! The problem with new helicopter pad lights

- Helicopter on Fire – Could accident investigators have learned more?

- The Ultimate Medical Helicopter – Selecting the right machine for HEMS

- Deconfliction in HEMS operations – Practical methods for keeping apart

- HEMS Landing Sites – Reliable places to drop your medics

- Planning to fail – The perils of ignoring your own advice

- 2D or not 2D – How much room do I need to land a helicopter?

- What is your left hand doing? How to use a 3-axis autopilot on helicopters

- My tail rotor pitches when it flaps! Why?

- Practical ILS explanation for pilots – the surprising way they really work

- Slow Down IFR! Are you speeding on the ILS?

- It’s behind you! Helipads and obstacles in the backup area

Leave a Reply