The Norwegian Air Ambulance lead the way in Europe for expanding the scope of what helicopters can do in emergency aviation. Through the application of technology, a deep understanding of their aircraft and a full grasp of the regulations, they have developed a system the outshines UK HEMS1. In this article, we look at six ways they have leaped ahead and how others might catch up. Specifically this article is aimed at the UK HEMS environment, but many European HEMS agencies are similarly far behind despite being in the same regulatory environment.

Many of these innovations are possible because of the regulatory changes that EASA2 has published over the last few years. Norwegian Air Ambulance have engaged with their authority and the EASA rulemaking team to shape the regulations that now exist, providing a ready made way ahead for the UK.

The major innovations we are going to cover are:

- LPV3 approaches using EGNOS4 for PINS5 approaches

- Reduced VFR6 minima for HEMS PINS approaches

- Low lever IFR7 routes for HEMS

- Weather radar for low level IFR HEMS

- Airframe icing limits in HEMS

- Weather data for HEMS

One of these is an absolute stand out that the UK really needs and it isn’t EGNOS. Let’s get stuck in.

Contents

LPV Approaches using EGNOS for PINS approaches

EGNOS is a form of SBAS8 applicable to the European region. When the UK left the EU, it also chose to leave EGNOS as well. Whilst there is hopefully a building momentum for the UK to rejoin permanently9, for now there are no LPV in the UK (also see our article on a related topic – LNAV/VNAV). This is of course not the case in Europe. Norway has fully exploited the opportunities this presents.

PINS Design Criteria

As we discussed in another article, the Swiss helpfully provide access to the ICAO Annexes and Manuals. In the Manual PANS OPS, the method for designing approaches is laid out. One option for helicopters is the Point-in-Space (PINS) approach which allows IFR departures and approaches to non-airfield locations. These allow crews to get down to as low as 250 ft above ground level under IFR using full 3D approaches.

The Norway Air Ambulance have deployed over 100 approaches up and down the country. Whilst some are to operating bases or hospitals, they are many that are set up in likely tasking locations so that crews can deploy and recover IFR, hugely increasing safety and the likelihood of reaching a patient. The approaches exploit all of the capabilities of the aircraft and the regulations. Let’s look at a few examples.

Approaching through terrain

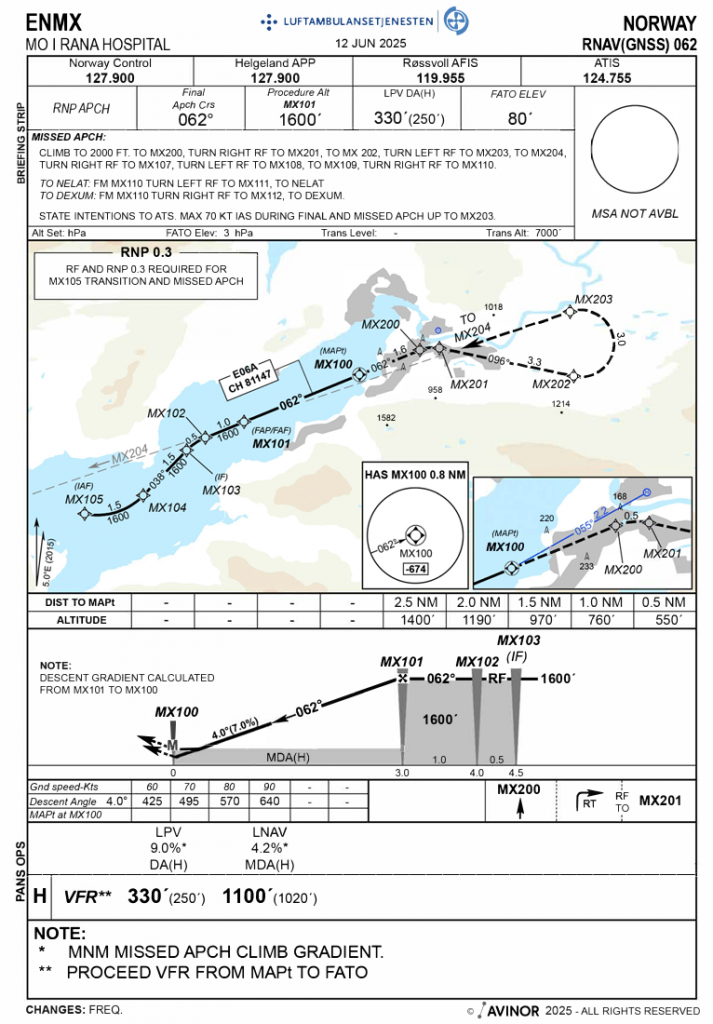

The hospital at Mo I Rana in Norway is a great example of what an LPV approach brings to PINS approaches. The hospital lies at the end of a fjord surrounded by steep mountains. The fjord provides a nice obstacle free environment, but the bracketing high terrain means a more pedestrian 2D LNAV approach is severely restricted. Note in the diagram below that the MDA for the LNAV is 1020 feet above ground level.

If we design an RNP 0.3 arrival and a slightly steeper 4 degree LPV approach the minima becomes 250 feet! That is a very practical height for UK weather! Of note, RNP 0.3 actually does not require EGNOS but the LPV definitely does.

There are a couple of other innovations for UK operators hiding on the chart. The missed approach uses a Radius-to-Fix (RF) leg to firmly anchor the ground path during the missed approach phase. Also note the slightly curved leg from MX105 inbound; this is another RF leg to keep the aircraft away from terrain. Finally the climb gradient required for the missed approach is somewhat sporty – at 9% that is double the climb gradient required for the northbound approach at Shoreham, UK, which is towards high terrain.

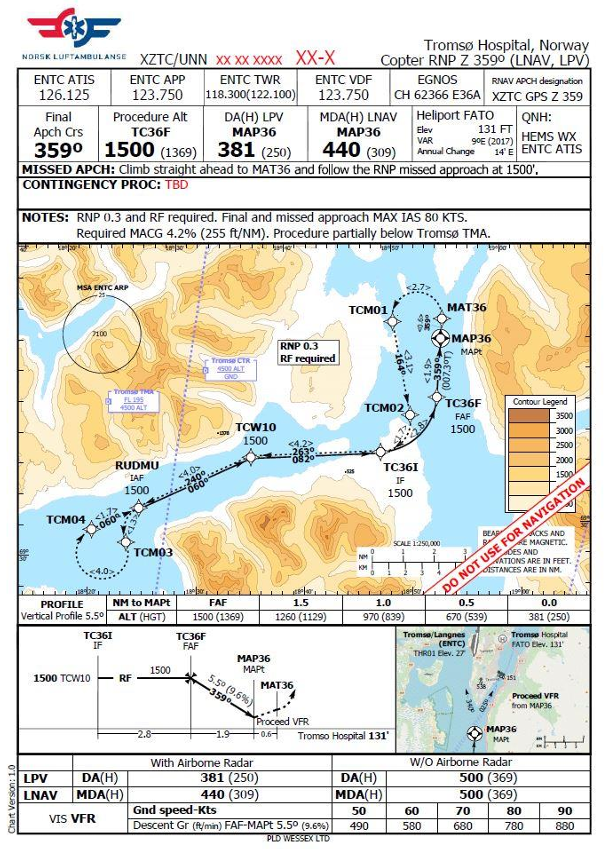

Curves before the FAF

The beauty of the PBN is that the curves can be used to squeeze the approach round corners. Note the turn in the example below immediately prior to the final approach fix at TC36F. Again a steep approach at 5.5 degrees.

Not just approaches

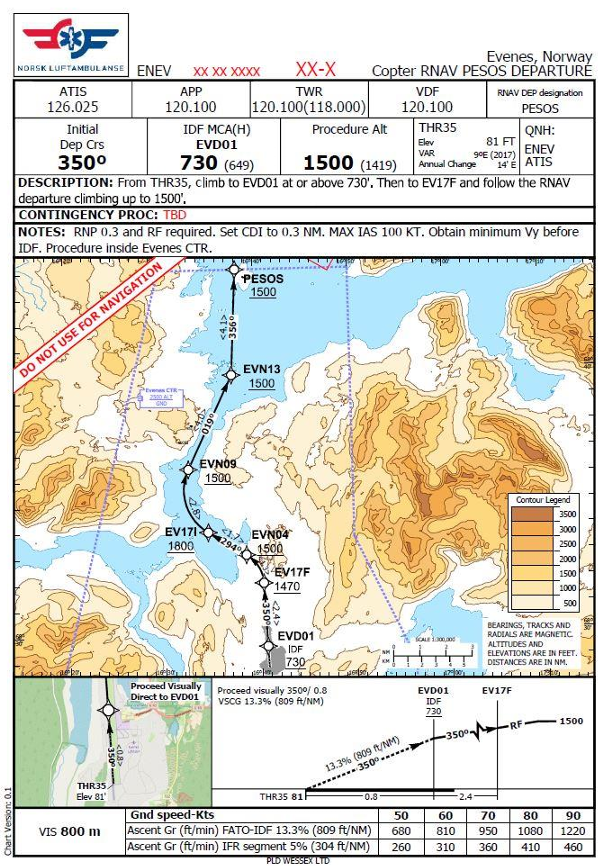

Just to highlight that when you have high terrain as in Norway, you may need some curves on the way out too. Take a look at the example below at Evenes. There is an RF fix soon after depature to keep the minimum altitude relatively low (although note the minimum does climb at little from 1500 to 1800 feet through this leg).

A draft version of the Evenes departure – EGNOS

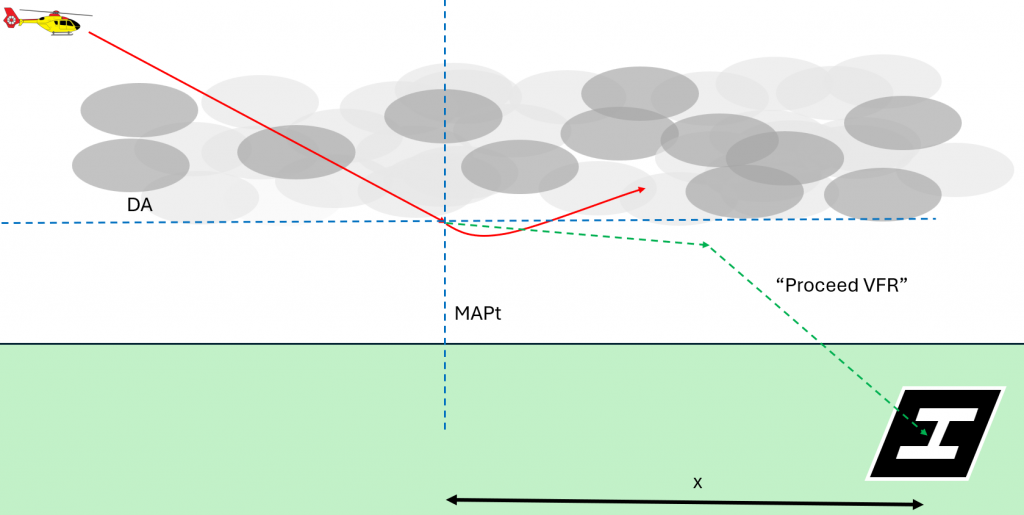

Proceed VFR – A problem

Now look back at the approaches to Tromso and Mo I Rana above. They each say “Proceed VFR” after achieving references at DA. But VFR in the UK is effectively a minimum cloud base of 500 ft by day and 1200 ft by night for HEMS. A 250 ft DA for LPV is brilliant but if I cannot achieve VFR then I have to go around. Bit useless. Well the regulators thought of that and made an exception.

Reduced VFR minima for HEMS PINS approaches

In the All Weather Operations update of the EASA regulations in 2022, changes were introduced which allowed for safe helicopter flights under IFR including PINS.

EASA Regulations

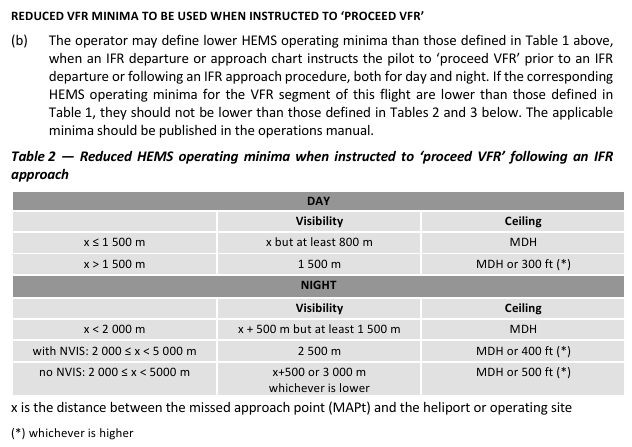

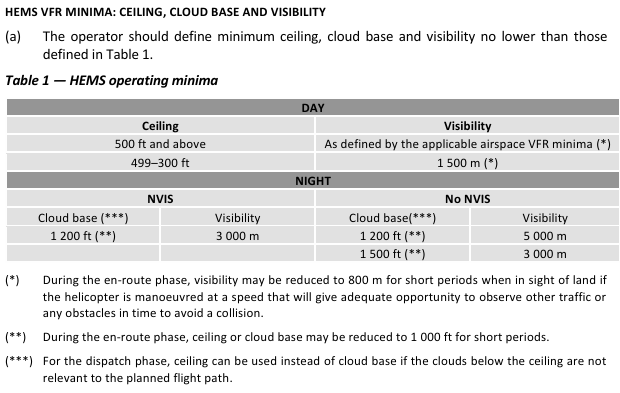

One important fact that was recognised during the consultation was that LPV approaches would include minimas as low as 250 ft above ground level and that continue VFR would not work with such low cloud. Therefore, the definition of VFR for this specific circumstance was amended. This can be found in AMC1 SPA.HEMS.120(a). Let’s look at them in full, then break it down.

There is no dressing it up – that is a complex regulation which is not easy to assimilate at a glance. A picture helps:

There is a responsibility on the operator to make a judgement within their own risk management SMS process to determine the appropriate minima. But say there was an MDH/DH of 250 ft, the minima by day could be as low as 800m with a ceiling of MDH. This makes using an LPV practical and most importantly a better option than trying to squeeze under the cloud layer VFR.

Comparison to EASA VFR HEMS minima

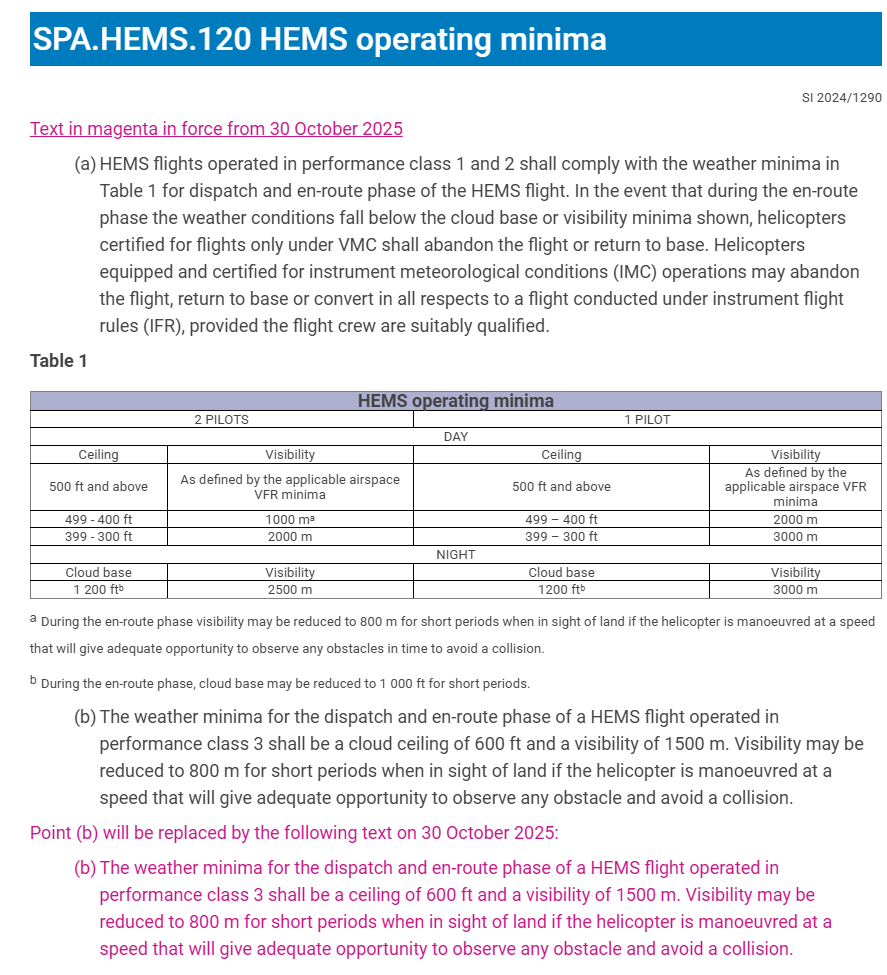

Actually it is not a huge leap below the extant VFR minima for day flying although they are much lower than normal at night. As a reminder the standard HEMS VFR limits are:

So the “normal” VFR HEMS minima could be as low as 300 ft cloud ceiling with 1500m visibility (and arguably 800 m visibility dependent on how you read the starred note!).

The starkest difference is in the NVIS minima. The normal minima are a 1200 ft cloud base (any cloud) and 3000 m visibility. With the reduced minima HEMS PINS VFR we can get down with minima as low as 250 ft (MDH) with 1500 m visibility at night with NVIS. That’s transformative. Night HEMS operations in marginal weather can be extremely challenging and having a method of recovering IFR allows a much safer option than pressing on in deteriorating conditions.

UK CAA Current Opinion

But wait, didn’t the CAA just adopt in October 2025 all the same AWO regulations that were introduced to Europe back in 2022/2023? Should not these same regulations be in place for UK operations?

No. We do not have these regulations – see UK SPA.HEMS.120. If you look at the consultation for AWO, the reasoning by the CAA was as follows:

This is slightly confusing as this opinion refers to a difference subpart of Part-SPA, Part SPA.PINS-VFR rather than the Part SPA.HEMS. This is because allows HEMS operators to use these reduced minima by default and so the regulation is inside SPA.HEMS. The more general SPA.PINS-VFR is for non-HEMS operators.

Nevertheless, the CAA removed both options rather than allow operators to adopt a risk based approach to using these reduced minimums. Thus the CAA regulated community is slightly stuck with PINS approaches that do not allow approaches in reduced VFR conditions at night. The risk the CAA are trying to mitigate by allowing PINS is the risk crews flying low under scudding cloud back to base. It is true that crews would be low under scudding cloud at the bottom of a PINS approach but the distance to base is very short and the aircraft will be at a known point for that short flight under the cloud.

The take up of PINS approaches has been extremely low, particularly paired with the lack of EGNOS and LPV. This creates a contradiction for many operators – the value of investing in the implementation of PINS / RNP 0.3 is not yet apparent but the real benefits will not come until operators have been using them for some time. Hopefully some operators can lead the way.

UK CAA AWO Opinion – Secondary Effects

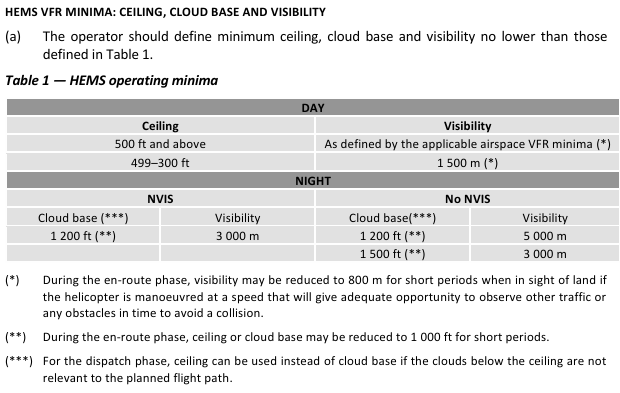

In addition to removing the option to use reduced VFR minimas for PINS, the remainder of SPA.HEMS was not amended in line with the original EASA consultation. Let’s compare the 2 VFR HEMS minima – EASA and CAA:

EASA HEMS VFR Minima

UK CAA HEMS VFR Minima

Note the differences in night operation have become NVIS/Non-NVIS in EASA rather than the 2 pilot/1 pilot separation of the UK CAA. The most crucial difference is in the notes.

In the UK, for cloud ceiling at 500 ft or above, the “…applicable airspace VFR minima” from Part SERA is 1500 m visibility by day. And yet I can go to 1000 m or even 800 m visibility (note a) if the cloud ceiling is lower (<499 ft). In addition in EASA, the allowance for reducing visibility briefly to 800m is allowed irrespective of performance class. And yet in the UK it is only allowed for Performance Class 3 operations which are less safe than Performance Class 1 and 2. This regulation does need some attention from the CAA!

Let’s move on to the low level IFR routes in Norway.

Low Level IFR routes for HEMS

So using the first two innovations, EGNOS LPV and reduced VFR minima, we can get down from IFR flight to visual flight. That’s nice, but how to get from base to the point of approach safely in marginal conditions. The first option is to go underneath but this is fraught with danger – see the crash of a Portuguese HEMS aircraft routing under a cloud layer where it hit a mast. But we don’t want to transit IFR too high because of icing in the cloud (see later). So we need a low level IFR route system that gets us through terrain.

RNP 0.3

To be able to thread our IFR routes through terrain, we need an accurate navigation system that is robust. Fortunately, there is a PBN navigation specification designed to achieve this exact thing: RNP 0.3. This specification, introduced in 2001, aims to achieve position within 0.3 nm of track 95% of the time. It needs a certified GNSS navigation unit but does not require SBAS. For example this RNP can be achieved by a GTN 750 equipped aircraft with Helionix or a Bell 429 with GTN 750.

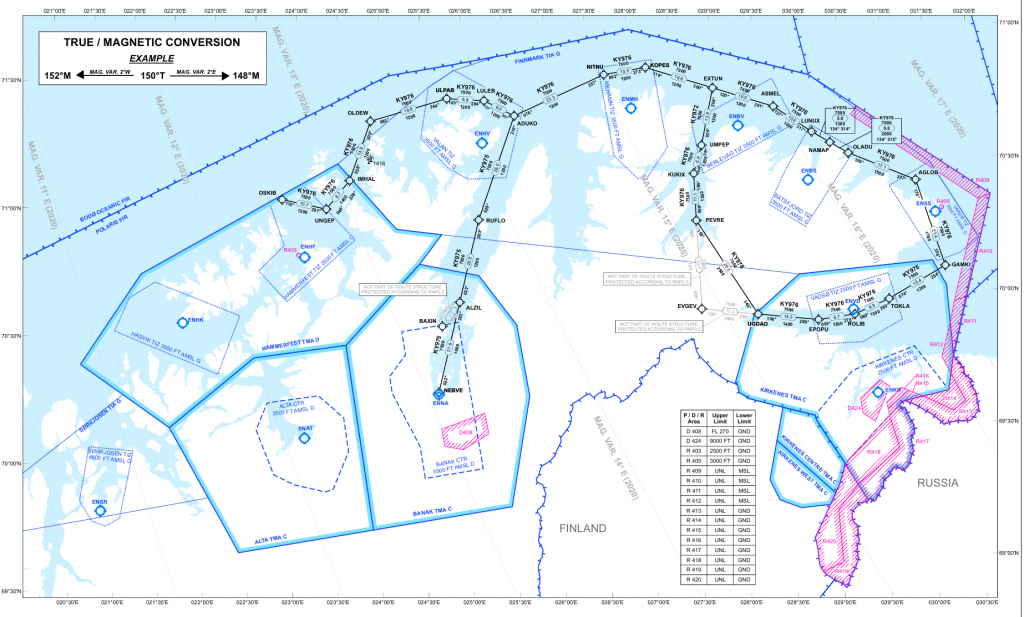

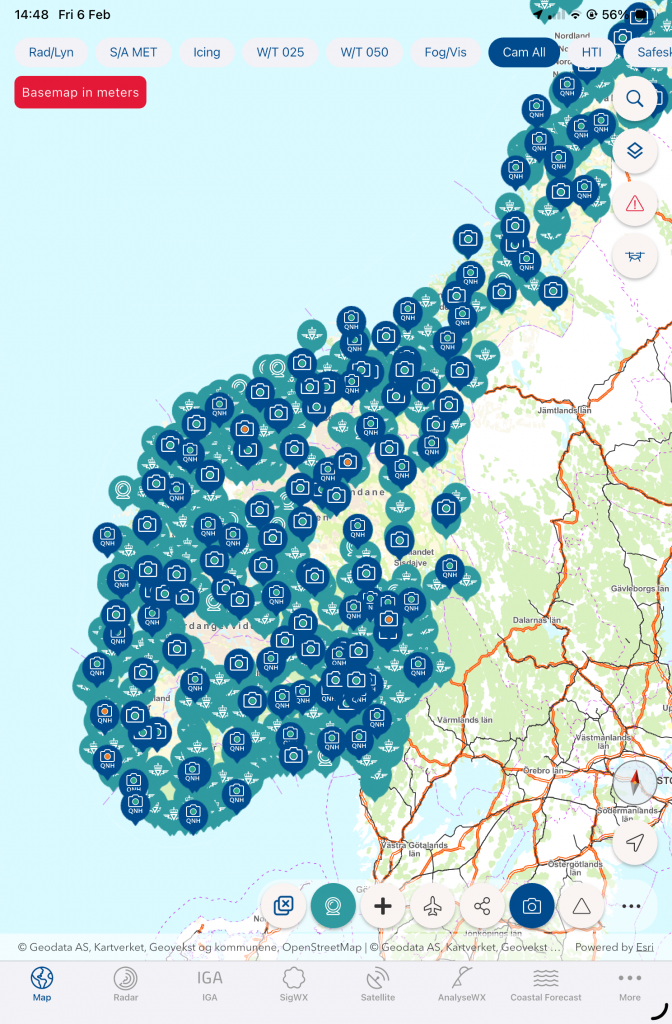

Norwegian Low Level IFR Route Network

The Norwegian Air Ambulance recognised that a comprehensive low level IFR route network would be required to link the bases to likely operating areas and then onto the hospitals and back to base. Without this comprehensive network the LPV innovation cannot be exploited.

The low level network stretches from the top to bottom of the country and nips into the back of fjords at strategic positions. A full map of the routes can be found in the Norwegian Helicopter AIP. Not all of the route network is RNP 0.3. It is tailored to the terrain and obstacles with a lot of the network just offshore being RNP 1. An example of the network is in the far north of the country. Note the proximity to Russia:

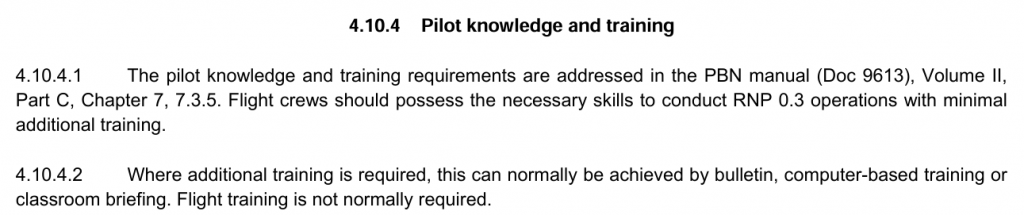

Training and Approval of RNP 0.3

Approval for RNP 0.3 operations is required in accordance with SPA.PBN. However, the associated regulation in both EASA and UK is somewhat unclear on the exact requirements for operators to demonstrate compliance with the regulations as most of the subsequent regulations and AMC deal with RNP-AR (RNP Authorisation Required) which is something different entirely. ICAO produce a PBN Operational Approval Manual but this is a bit sparse on an approval specifically for just RNP 0.3.

Fortunately for the training side of the house, it is relatively simple for crews to learn how to operate under RNP 0.3. Indeed the ICAO PBN Operational Approval Manual states:

GPS Jamming

With our PINS departures we can get from our base, transition to IFR using a PINS departure, fly down the fjords, pick up a LPV and arrive near scene then repeating the performance to get to hospital and home again. However, the whole system relies on RNP in various forms.

Currently this is all based on GNSS. In our current world, reception of GNSS is not guaranteed. The Norwegians are particularly aware of this due to the borders in the north of the country. Indeed, the jamming of GNSS is so frequent, pilots do not need to even report the problem any more – Stops Registering GPS Disruptions in Finnmark, Northern Norway.

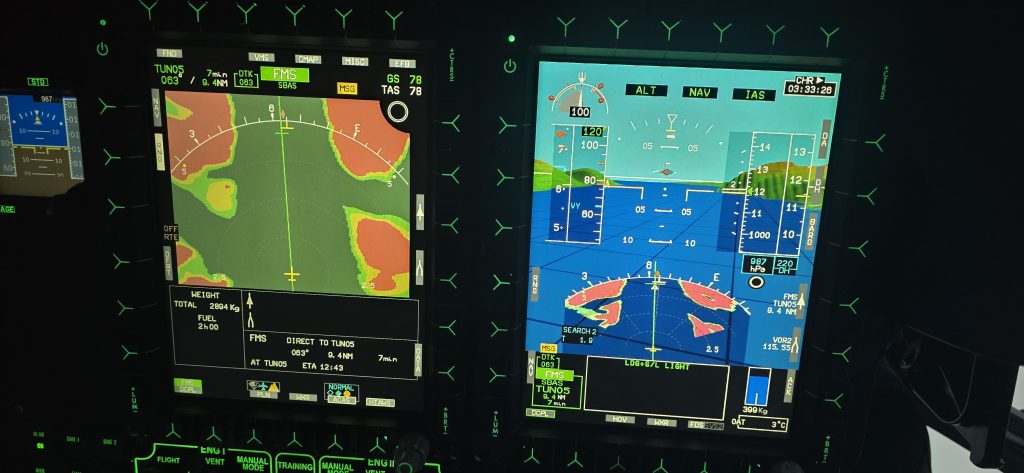

There needs to be some resilience to this threat. Imagine being in a fjord, below the level of the mountain tops but fully immersed in cloud. The loss of GPS leads to not only losing the position of the aircraft but also most parts of the Helicopter Terrain Awareness and Warning System (HTAWS). Note in the image below that the left GTN 750 is completely jammed.

Weather Radar in HEMS

In mitigation for the potential loss of GNSS reception due to jamming, Norway Air Ambulance have fitted weather radars across their fleet. This allows a safe recovery to visual conditions in the event that GNSS-derived position information is temporarily lost. The typical setup of the cockpit is shown below – note this image is from the simulator used by Norway Air Ambulance so the radar image is simulated. However, note the pilot in the image above has weather radar overlaid on his screen and it matches how the simulated radar is shown in the image below making the simulator a very powerful training aid.

Note in the image about, the terrain on the centre screen is from HTAWS, as in the terrain in the background of the right screen (on SVS view). The terrain at the bottom of the right screen is from the weather radar. It is appropriately setup in terms of scaling, mode and antenna tilt such that there is a good correlation between screens and sources. This allows the crew to seamlessly transition from HTAWS/GNSS to weather radar in the event of jamming to continue an approach or turn back as appropriate.

But are we missing something here? There’s something about Norway that makes flight in cloud challenging for helicopters – it is reasonable to expect it to be cold and therefore icing is a problem that needs to be mitigated or avoided entirely.

Airframe Icing in HEMS

Ice is water that has frozen. So we could reasonably say that icing can be expected to exist at 0 degrees Celsius.

But take your helicopter flying in a bright clear winter’s day at minus 5 degrees Celsius and you do not accumulate ice. The missing component is water. Ok, so we can say icing exists when the temperature is zero degrees or below and there is moisture present.

Well that is not true either. You can fly through snow or ice crystals and not necessarily accumulate ice on the airframe. Conversely, you can accumulate ice in the engine intakes at temperatures above zero during to the cooling effect of the venturi of the intake. Additionally ice can form from snow in the wrong conditions – see Pilots Who Ask Why article on the H145 engine flameout due to icing.

Icing – A complex definition

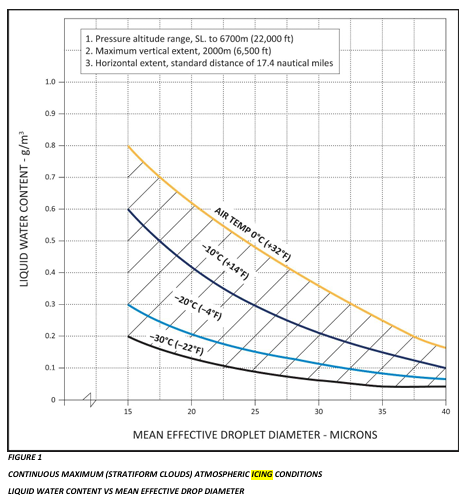

As can be seen defining icing is a complex endeavour. It starts with the certification of the aircraft. This is through either CS-27/FAR 27 for “small” helicopters <3175 kg or CS-29/FAR 29 for “large” helicopters >3175 kg (EASA/FAA respectively). There is a whole appendix to CS 29.1419 that deals with what constitutes icing conditions which revolves around 3 parameters: temperature, liquid water content (LWC) of the air and droplet size.

These charts are quite complex to understand and are not suitable for use by the line pilot so it would be quite helpful for manufacturers to provide some guidance. They generally do not!

Known Icing Conditions

Pickup any civilian flight manual for a helicopter that has no icing clearance and the language is pretty similar:

- H145 – The following are prohibited – flight in known icing conditions

- Bell 429 – Basic helicopter is approved for…non-icing conditions

- AW109E – The helicopter in the basic configuiration is approved for…non-icing conditions

- MD600N – Flight in known icing conditions is prohibited.

Not one of these manuals goes on to define what “known icing conditions” is! This is generally for the operator’s management to define and they typically fall back on the simple “Flight below zero degrees with visible moisture reducing visibility below x metres” or something similar.

But what if we could tell what were icing conditions? We need better weather information! Time for our last innovation.

Weather Data from HEMS

In order to exploit all of the innovations covered so far, we need accurate weather information for where we are actually planning to fly. Relying on airport TAF/METAR is just not good enough. An airport 20 miles away and 600 ft higher than you will almost certainly not be relevant enough! Helicopters operate at low level away from airports and we also now want to fly in cloud at low level – we need better information.

Norway Air Ambulance have a 2 pronged approach to this: accurate tailored information from the national weather service and organic home-grown data produced from bespoke weather stations and webcams. They bring all this together in an app called HEMS WX which is available on the AppStore or Google Play. You would need permission from Norway Air Ambulance to use it though.

Norway HEMS Weather Information Provision

As a HEMS operator, what weather do I want and how should it be optimised for me? One point to start with (UK Met Office take note with your new MAVIS service) is I generally care about the lower 10000 ft of atmosphere but in particular the lowest 3000 ft in 500 ft increments. A weather tool tailored for fixed wing operations is generally going to unsuitable for helicopter pilots.

The weather and data a HEMS pilot really needs to know about is:

- Precipitation

- Low level winds

- Fog / visibility

- Cloud

- Hazardous conditions (CB, thunderstorms etc)

- Icing

- Sunrise/sunset

- Night lighting levels (NVIS operators)

- Tides (for shore operations)

I want all that in as much detail as possible, as up to date as possible and spread all across my operating area. I also want to predict.

Norwegian Weather Products

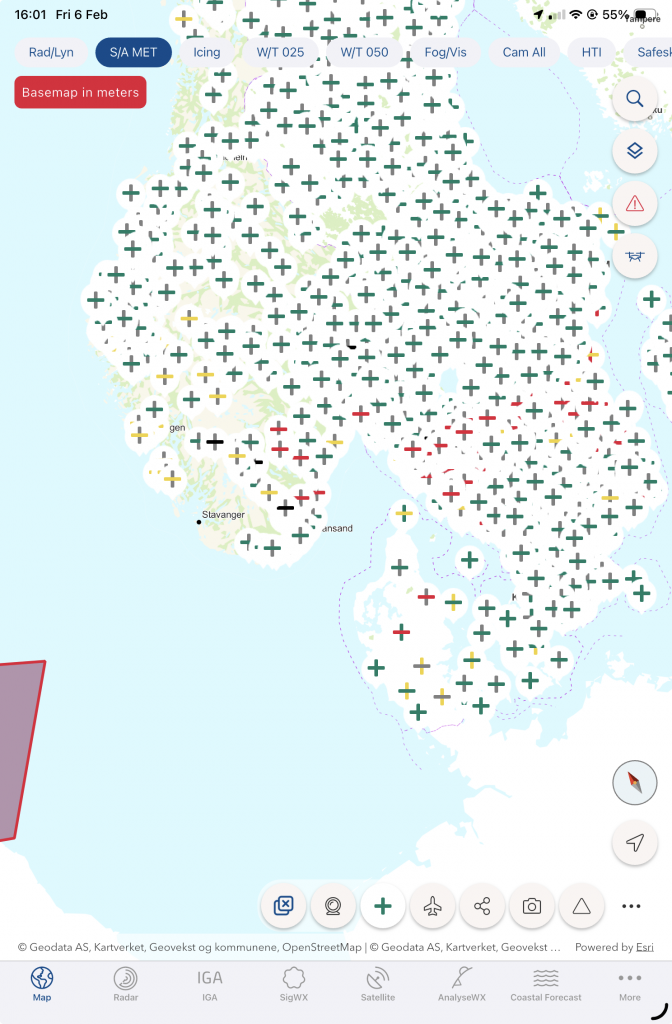

Assuming as a baseline that Norwegian weather products match what is currently available in the UK through HeliBrief or MAVIS we get area forecasts, cloud overlays, visibility overlays and wind charts. What extras do the Norwegian’s have as national “products”?

Route cross-sections

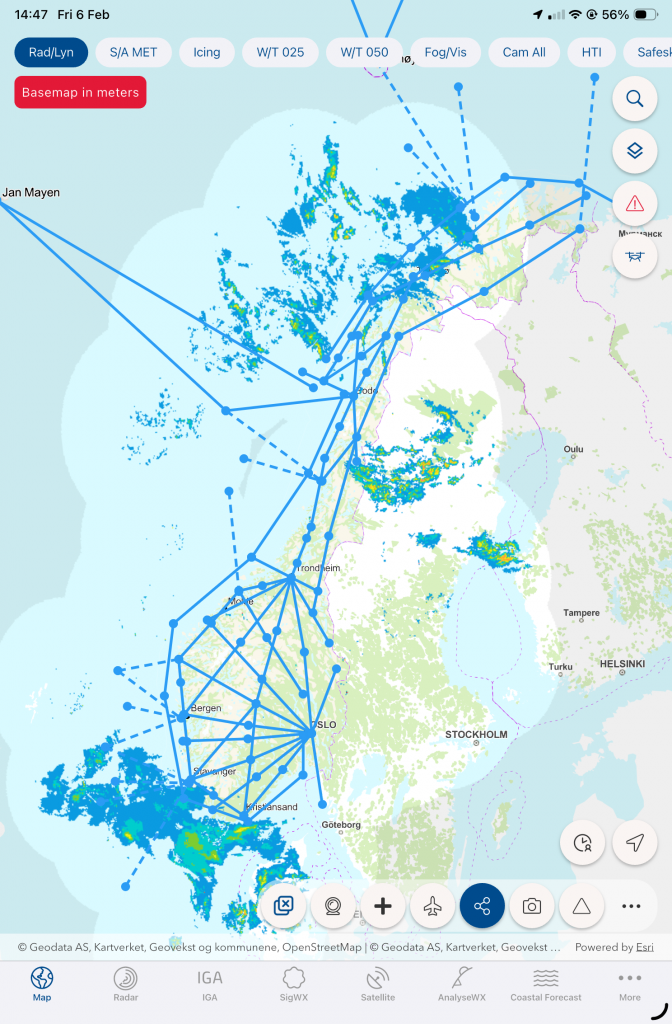

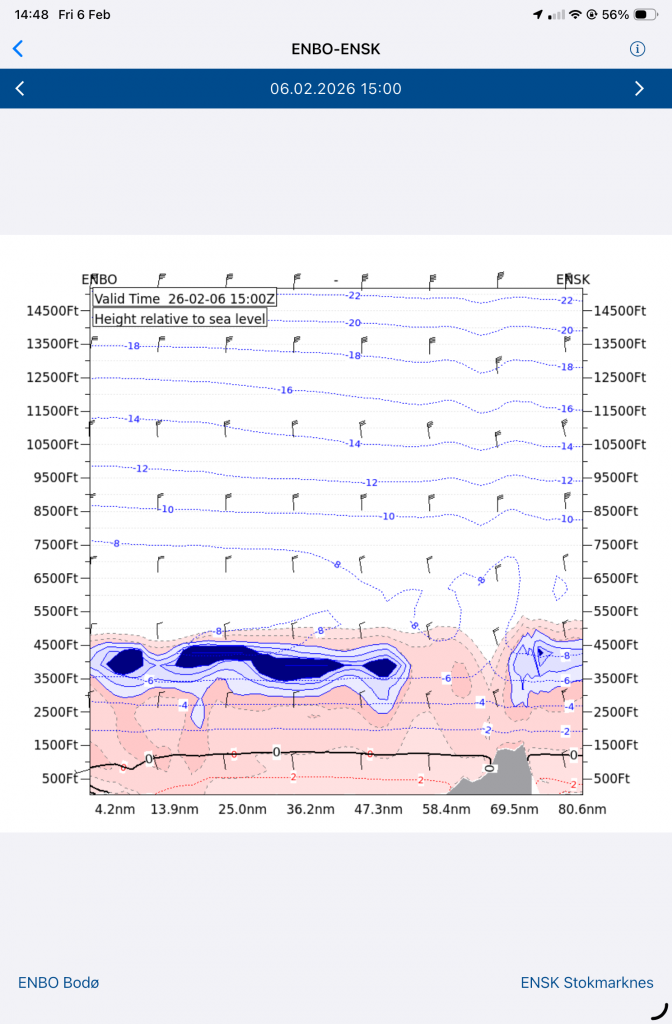

Remember the low level IFR route structure? It would really helpful to get a cloud and icing forecast for each route for the typical altitudes for a helicopter. Let us draw out some routes on a chart – see the light blue lines below.

Now I want a forecast for a particular leg. Let’s focus on the lower atmosphere, let’s us shown terrain in grey and put the distance along the bottom. Add colour shading for relative humidity (ie cloud) with temperature and colour in the areas of icing based on the definitions above. Now I know if I can fly this route IFR or VFR and what altitude band I need to avoid to miss the icing. Note, the cloud is sub-zero but the meteorological model shows it will not cause icing – only the heavily shaded areas present a risk. This is a huge leap in knowledge over the simplistic way icing is described by most operators.

Location Cross sections

In addition, point location cross-sections can be obtained with a time reference along the bottom – these are made manually in the UK for military airfields but the Norwegian using met data to automatic produce the chart.

Direct weather station access

The weather service uses a lot of raw data to produce its products. This requires lots of weather stations to gather the data. These have some very valuable data which might be just near where a HEMS task is. It would be great to be able to access this raw data. No problem, these are available to Norwegian Air Ambulance crews providing basic data such as temperature, humidity and visibility.

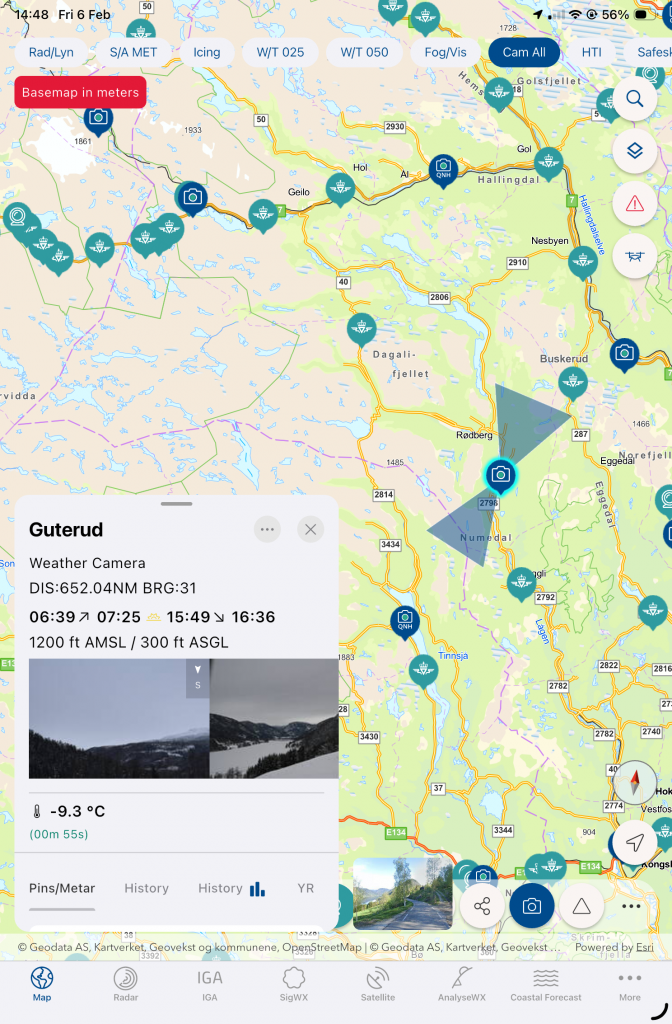

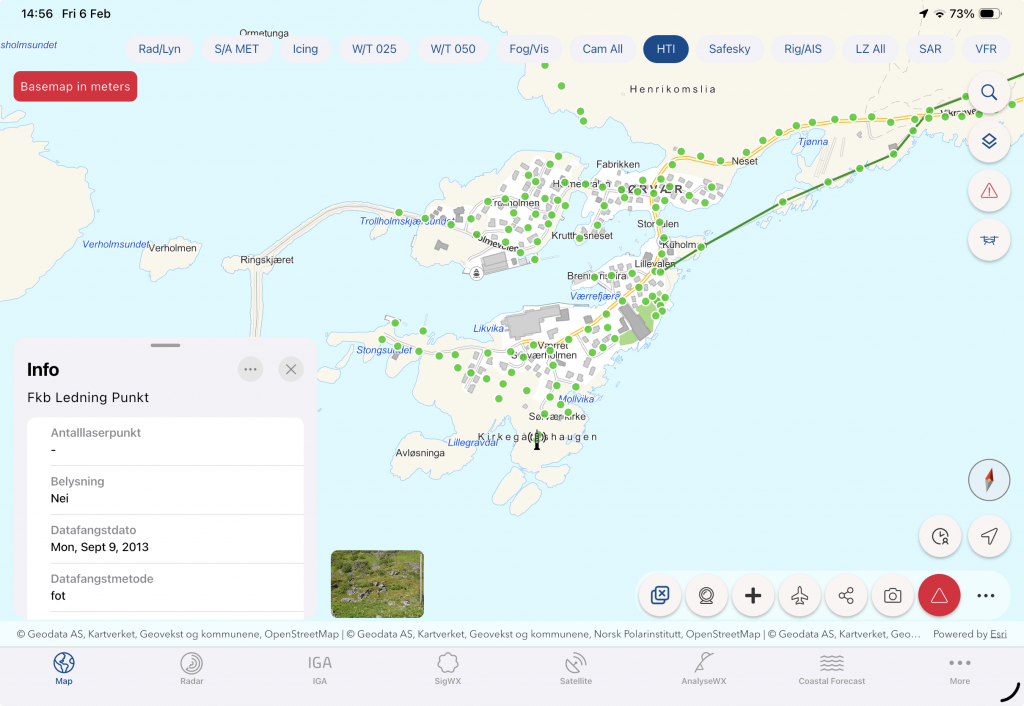

HEMSWEATHER System

These national products were great but what could help pilots make the right decisions like they were already at scene? One pilot from the Air Ambulance, Jens Fjelnset, developed a system using strategically located and connected camera boxes to provided reliable up to date information on the conditions across Norway.

Camera boxes

Each box contained up to four SLR cameras with some basic weather sensors and connectivity to the internet. The images, captured every 15 minutes, can all be accessed from an app which shows where the camera is pointing.

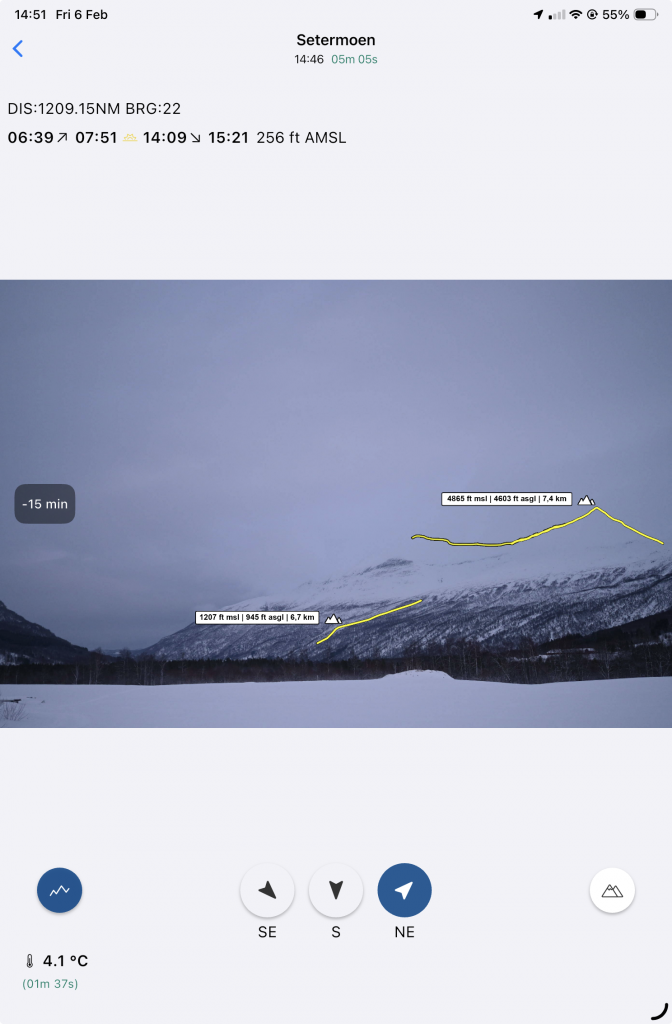

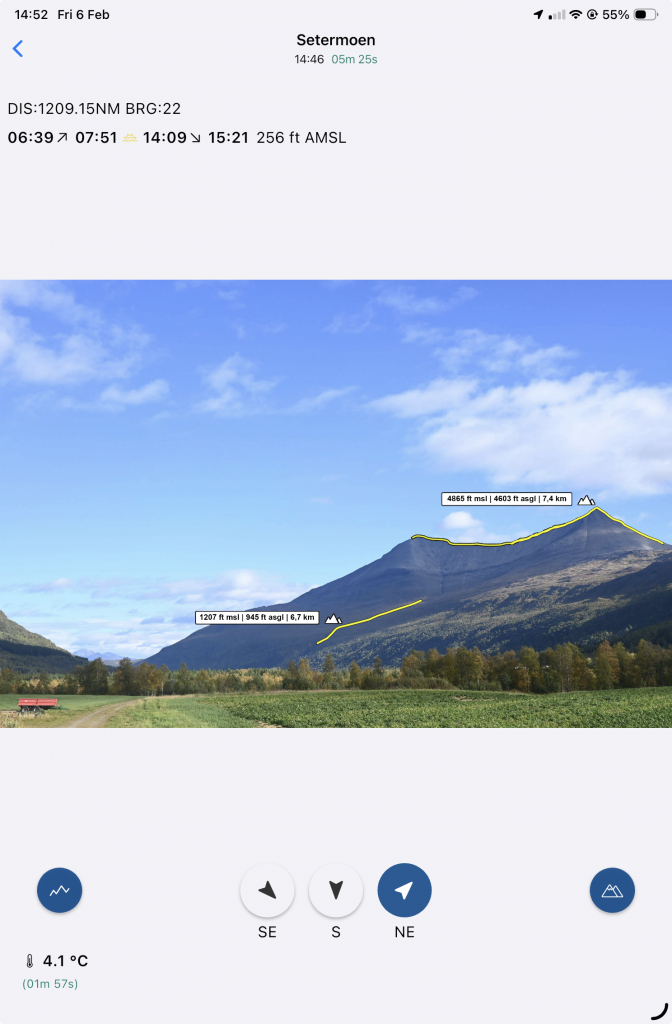

HEMSWEATHER images

The images are shown with optional references for the terrain you should be able to see along with elevation and distance data.

The pilot can then make an assessment of the local conditions (including light levels). A reference image is provided so you can see what it should be like. Note the twin peaks which are invisible in the top picture.

Other webcams

So this extra data and images are great, but what about some more data? Let’s use what is already there:

In addition to the bespoke webcam system, it would nice to access the extant traffic cameras from the road network. No problem.

Bringing it togehter – HEMSWX App

All this weather data is great, but there is other data we need as HEMS pilots. Wirestrikes are a constant threat in Norway and there have been some fatal accidents in HEMS – most notably an EC135 that hit wires in 2014. Norway Air Ambulance are acutely aware of this hazard, so why not provide the data in the app that has been built to distribute the extensive met data? While we are it, what about Google Maps Streetview data?

Let’s add some basic mission planning tools and voila! The HEMSWX app has all of the data mentioned with most of it available offline which makes it ideal as an EFB application.

Summary

We have looked at six main innovations that Norwegian Air Ambulance have introduced that put them streets ahead of other operators. What they have done to exploit the possibilities generated by technology and by new regulations is astonishing.

But of all the six innovations, one stands out. The HEMSWX app is what is needed urgently in UK HEMS to improve the situational awareness of UK operators. If the appropriate data such as HEMSWEATHER cameras, the route forecasts, point cross-sections and traffic cameras could be introduced for UK HEMS, the transformative effect it would have on operations cannot be underestimated.

One day!

Why not check out our other articles?

- Keeping up with the Norwegians – Six amazing innovations for UK HEMS

- LNAV/VNAV (SBAS) – Are they approved for use in the UK?

- Helicopter 2D IFR approaches – Is CDFA the best choice?

- Understanding Helicopter Flight Manuals – Everything you need to operate safely

- Post Maintenance Flight Tests – How to avoid fatal traps

- First Limit Indicators in Helicopters – Deadly mistakes to avoid

- Bad Vibes – How to report vibrations on helicopters

- Autopilots, cross-checks and low G in helicopter unusual attitude recovery

- Expert site surveys – Improving the assessment of onshore landing areas

- Lights, helipad, action! The problem with new helicopter pad lights

- Helicopter on Fire – Could accident investigators have learned more?

- The Ultimate Medical Helicopter – Selecting the right machine for HEMS

- Deconfliction in HEMS operations – Practical methods for keeping apart

- HEMS Landing Sites – Reliable places to drop your medics

- Planning to fail – The perils of ignoring your own advice

- 2D or not 2D – How much room do I need to land a helicopter?

- What is your left hand doing? How to use a 3-axis autopilot on helicopters

- My tail rotor pitches when it flaps! Why?

- Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) ↩︎

- European Union Aviation Safety Authority (EASA) ↩︎

- Localizer Performance with Vertical Guidance (LPV) ↩︎

- European Geostationary Overlay Service (EGNOS) ↩︎

- Point-In-Space approaches (PINS) ↩︎

- Visual Flight Rules (VFR) ↩︎

- Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) ↩︎

- Satellite Based Augmentation System (SBAS) ↩︎

- Some agencies in the UK are pushing for a temporary re-joining of EGNOS. This is the wrong choice as it will disincentivise UK operators and airports from re-deploying LPV through EWA with EGNOS. We need to rejoin permanently. ↩︎

Leave a Reply