The need for separation

Typically, a helicopter used in the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) has a crew that can manage one critically ill patient at a time. Where an incident has multiple casualties needing a critical care response, multiple helicopters can be tasked to the same incident. In addition, other types of emergency aviation can be in use at an incident such as police helicopters or drones. Keeping all this aviation apart in the sky is key to maintaining safety in challenging conditions.

In this article we are going to look at:

- The aim of deconfliction

- The equipment we have to support deconfliction

- The means we have to achieve deconfliction

- The ways we should deconflict

Aim of deconfliction

At a complex multi-casualty incident like a minibus crash, many different emergency response agencies can respond. Not all of these agencies will be airborne but the skies can get very crowded. The key driving factor in generating confliction is the urgency of the situation and the magnetism of the incident – everyone wants to get to the same place as fast as possible.

In an idealised world we would have the opportunity to have a brief before the mission with every aviation asset involved and agree how we were going to keep apart in the sky while achieving the mission. This simply is not practical in emergency aviation so we need a set of simple tools to allow us to assess the situation dynamically and respond accordingly.

The tools we have need to achieve the following:

- Separation of all aviation assets

- Maintenance of speed to achieve the mission

- Simplicity for instant use

- Flexibility for the unexpected

Equipment

In order to create some usable deconfliction tools, we need to know what we have to work with. In civilian emergency aviation, we will typically have access to the following:

- Aircraft flight and navigation display – altitude, speed, heading, track and position

- Emergency services radios – in the UK and Europe these are radios based on the Tetra system which operate over the cellular network

- Air traffic radios – Operating in the VHF aviation band

- Transponders and electronic Conspicuity – Mode C/S transponders and ADS-B tranceivers

- Electronic Flight Bags (EFB) – Tablet based navigation system with collaboration tools like position sharing and messaging – eg ACANS

Means

So how can we deconflict? There are many layers of defence.

Lookout

The simplest solution is to look out the window, see each other and avoid flying into each other. This might even work if visibility is good and the crew sees the right aircraft and correctly interprets their intentions. However, there are so many pitfalls – late acquisition of target, misjudging intentions, incorrect distance judgement and human performance limitations. A deconfliction based solely on lookout is likely to end in reduced separation and possibly collision. Not something to use in isolation!

Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems (ACAS)

Modern emergency aviation will generally have some form of aviation transponder on board. With a Traffic Awareness System (TAS) or Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) on board, a crew can electronically see the position of other airborne users. The crew can build a good mental picture of local airspace and place transponding aircraft in that world to work out how to avoid hitting the other aircraft. However, the systems have there limitations.

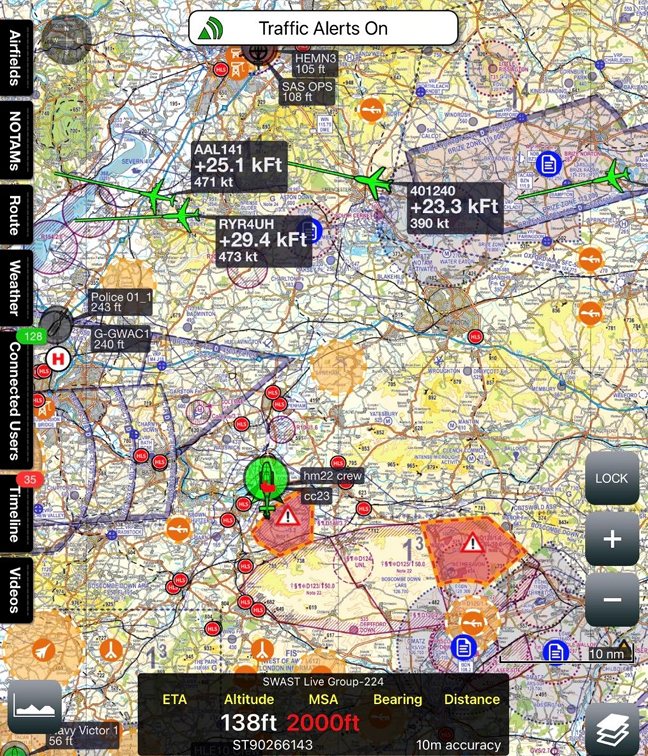

Electronic Conspicuity is only useful if the transmitting and receiving aircraft have compatible equipment and that the system is interpreting the signals without error. Whilst pretty much all UK and EU emergency aviation has traffic awareness systems in some form, they are still fallible, particularly in direction due to the nature of how the system works this out. They are much better vertically provided the altitude system is working. We will come back to this. However, as shown below, it can sometimes be a little confusing on a very busy day!

Mission planning tools and EFB

One of the huge advances in emergency aviation in recent years, has been the introduction of moving map based tablet mission planning tools for navigation, communication and document storage. In the UK, the primary system in use for all emergency aviation is the ACANS system produced by Airbox Systems (Airbox Systems – Services – Aviation – Aviation). This provides a tablet-based moving map which is overlaid with the position of all other participating users.

At a glance crews can see the position of all other emergency aviation using the ACANS system. This dramatically improves situational awareness and allows crews to see the relative position of other users with position data being transmitted over mobile networks. It relies of the ground based mobile network and that participants are using ACANS but this is fairly universal amongst Police, HEMS and Coastguard aircraft. The accuracy of the aircraft’s position altitude and speed is very good with clear indications (greying out) if a position is old or not updated. Optionally ADS-B data of other air traffic can be overlaid using a connection to an ADS-B receiver like a uAvionix Sky Echo (SkyEcho – uAvionix).

So we can deconflict easily now that we can “see” each other. Mission accomplished? No! The intent of the other users is unknown. Are they coming to the same task as me, what medical team are they bringing? Who is going to arrive first? What are their intentions? Something is missing!

Communication

The missing link here is communication. Without an effective 2-way discussion, we are not going to produce an effective deconfliction plan. We have several means of communicating which have some advantages and disadvantages:

Air Traffic Radios

We use air traffic radios all the time to talk to ground-based air traffic controllers and radio operators. For example in the UK, I can talk to local airfields or a national controller in London or Scotland who can provide me with a service. The other emergency aviation assets will do the same. However, this is not an appropriate medium for developing a deconfliction plan at scene – air traffic frequencies are set up as hub-and-spoke systems with communications going through the controller – direct air-to-air chats are not welcome at all!

Fortunately, in the UK and across the globe a dedicated frequency is allocated to allow on-scene discussions between aviation assets. This is on frequency 123.1MHz – called “Scene of Search”.

Discussions can flow freely on this frequency to co-ordinate a deconfliction plan. Whilst accuracy, brevity and clarity are still essential, a few deviations from standard R/T phraseology can be used to get the point across.

Emergency Service Radios

The Emergency Services in the UK and Europe use Tetra-based radios which operate over the mobile network and in point-to-point direct mode. Typically when a radio is operated, it transmits on a regional network and the transmission is received by every other radio tuned to that network. This allows easy communication between participating assets in a regional area. In some instances this is the primary means of communicating for all mission related chat. For local assets this can be used alongside “Scene of search” for deconfliction. A direct point-to-point call could also be made provided the other persons number was known.

However, as soon as any asset from another region or user group (eg Police, Coastguard) enters the mix, the system does not support direct chat. Each asset will be on a separate network and unable to talk together unless a dedicated sub-network for the incident is setup (which does occasionally happen). Therefore a useful communication channel with severe limitations.

On the flip-side, one key benefit is that emergency services radio allow communication when the aircraft is shutdown. A handheld radio can be used to talk to an aircraft.

Mission Planning Chat

Another novel feature of mission planning systems is the text based chat feature which is often built in (called “Timeline” in ACANS). This allows multi-way chat between users in groups or individually. It has the advantage of clarity as it is easier to read than listen and has permanence – the messages can be read at any time and can be reviewed later. As for emergency services radio, the limitations of communicating within defined groups means it does not work if outside assets take part. Some users may not use the chat function routinely and may not have capacity in small crews to type responses. So again, useful with limitations.

Best medium for comms? – Scene of search – 123.1 MHz

From these deliberations we can see that Scene of search is the go-to communications tool for deconfliction. The frequency is allocated for this task across the globe incidentally. But what is the plan!

Deconfliction Plan

So we have decided to communicate in a clear concise way. What are we going to use as our tools? We have the following options:

- Time deconfliction

- Horizontal deconfliction

- Vertical deconfliction

Time

We only collide if we are in the same place at the same time. So why not sequence ourselves in? The first requirement is a common point of reference. Generally, the hour of the day is not going to matter. We are planning for something that will happen in minutes not hours – British Summer Time is not an issue here. All aircraft in the modern era have GNSS which should provide a common time reference. Working to the nearest minute is usually sufficient.

But what about elapsed time? With modern navigation systems our time to go to a waypoint should be readily available. “I’m 5 mins out!” might be a useful call to another aircraft, allowing the comparing of arrival times. However, this needs to be approached with care. When arriving in similar points in the sky a rounding error could be critical. If we are going to the nearest minute, up to a 30 second error is immediately introduced (equivalent to 1 nm at typical cruise speed). This is huge in airspace terms. It is also fairly tempting to provide approximations when conducting a rapid fire conversation in this environment “I’ll be there in about 5 mins!” could be plus or minus 1 or 2 mins (now up to 4 nm in error). This could be deadly.

With this in mind, it is vital to be accurate and honest in these circumstances. There is a huge pressure to get to scene quickly and perhaps even some rivalry to be first. This tendency needs to be tempered. Accuracy in time for time based deconfliction is critical

Horizontal deconfliction

So if time deconfliction is not infallible lets occupy different bits of the sky. Suitable horizontal deconfliction relies on a common understand of the scene to which the aircraft are converging. In some cases it might be simple: “I’ll stay on the north side of the valley, you stay south”. But sometimes perception may be different for each crew – which valley!?

Geographical features may be used for deconfliction. The features used must have the same qualities as navigational features: easy to identify, unique in the environment and usable from the air. A road might be useful, but only if it the only road that fits the description from both cockpits. “…the north/south road…” you think is ideal might have a parallel twin which is more obvious to the other crew. “The M5 motorway” might be more useful. Similar issues occur with rivers, roads, towns and hills.

Sometimes, convenient line features may not be present and we may need to use point features. For example, “I’ll hold south of the church until you have landed”. This may work but it can be very easy to lose track of relative compass directions when orbiting in close proximity to a site.

Horizontal deconfliction has its limitations too!

Vertical deconfliction

Vertical deconfliction provides a good tool for staying apart. Again, we need a common reference to work from. Generally we will be on QNH setting on our barometric altimeter, but we need, through communication, to ensure we on the same setting. This should be an early part of the conversation between crews. Provided there are no airspace or weather related restrictions a 3-500 ft band per aircraft should be sufficient. The first to land, as worked out between crews, should be the lowest. Everyone stays in their band unless absolutely certain the other aircraft is no longer an issue (eg landed or deconflicted laterally).

We could also use radar altitude. However, due to natural undulations in terrain and obstacles, this may not provide a common reference. An option, but best kept to a fairly flat environment.

Other Considerations

There are a few other issues to consider.

Drones

Deconfliction with unmanned aviation will become increasingly relevant as technology and proliferation develop. There is extensive use of drones in emergency aviation from small man-portable machines to larger heavy fuel aircraft. Regrettably, the preferred communications tool of VHF radio is only used by some drone operators. It is highly likely that supporting agencies need to be asked to ground unmanned machines whilst helicopters operate at a scene as direct comms with a drone pilot is unlikely. A particular hazard exists when responding to incidents in military operating areas where extensive use is made of drones. Early engagement with the controlling agency will be necessary.

Weather

As briefly mentioned above, the weather can have a dramatic effect on the capability of crews to deconflict. Not only might visibility be reduced, but the vertical scope to deconflict may be heavily restricted by the cloud base. Crews should anticipate using time based deconflict and electronic means more heavily in poor weather conditions.

Night

At night, a robust deconfliction plan is even more critical. Vertical deconfliction is even more important when ground features and depth perception are harder to find and use.

Debrief

Working with crews from different regions, in different roles and with different equipment is likely to generate many challenges. Whilst establishing a common understanding is essential, if may occasionally not quite work out. On the other hand, it may go beautifully. It is critical to take the time after a multi-agency event to check how it went for all the players involved. Your perfect grasp of the situation might be exposed as a complete fiction after a short chat with another pilot. A hot debrief on scene can often de-risk the departure so wandering over for a chat can be a brilliant use of time. A more thorough chat after return to base may also throw up some lessons for next time.

Conclusions

Separating aviation in the highly challenging emergency aviation environment is a non-negotiable necessity. Looking at the available tools and methods, we can draw some conclusions:

- Communicate, communicate, communicate – a shared understanding of the situation and the deconfliction plan must be established at an early stage. If in doubt, ask.

- Use a dedicated air-to-air channel – 123.1 MHz is a great starting point

- Establish common references – as a minimum share which QNH you are using and chose clear, unique deconfliction features

- Use vertical deconfliction where possible

- Adapt to the conditions – use alternate deconflict methods if the normal ones are impossible

- Debrief with other crews – take the time to learn from each multi-agency event

Check out my other articles:

- Post Maintenance Flight Tests – How to avoid fatal traps

- First Limit Indicators in Helicopters – Deadly mistakes to avoid

- Bad Vibes – How to report vibrations on helicopters

- Autopilots, cross-checks and low G in helicopter unusual attitude recovery

- Expert site surveys – Improving the assessment of onshore landing areas

Leave a Reply